Indigenous stories reveal the science of the world around us

March 22, 2022

March 22, 2022

Indigenous stories hold clues to hydrological and geographical features, providing insights into the science of the world around us.

Dr. Shandin Pete, assistant professor of teaching in UBC’s department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences, investigated a story that may have helped his Seliš ancestors judge when to safely cross rivers along the buffalo trail. Today on World Water Day, Dr. Pete explains what scientific clues Indigenous stories reveal.

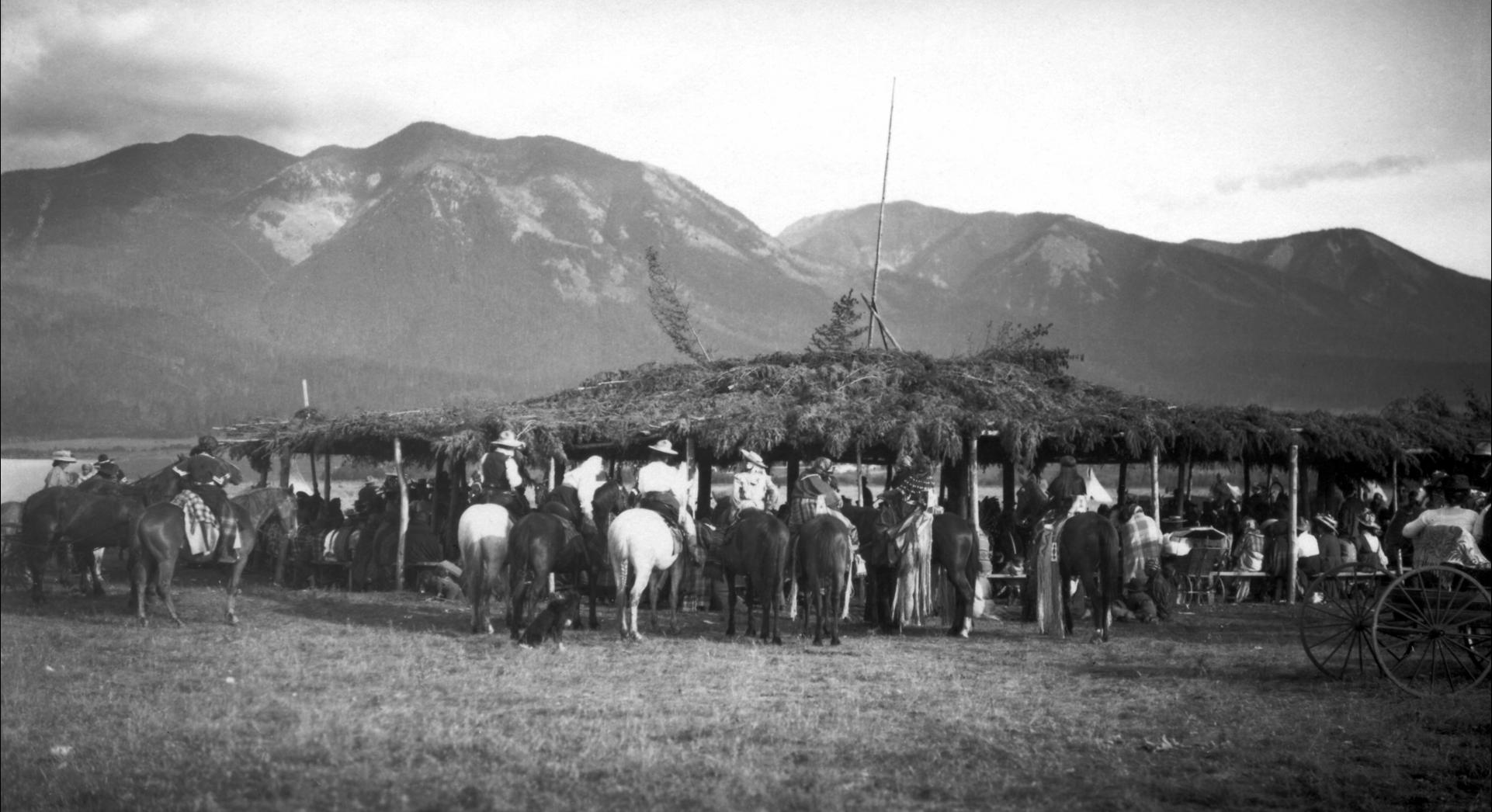

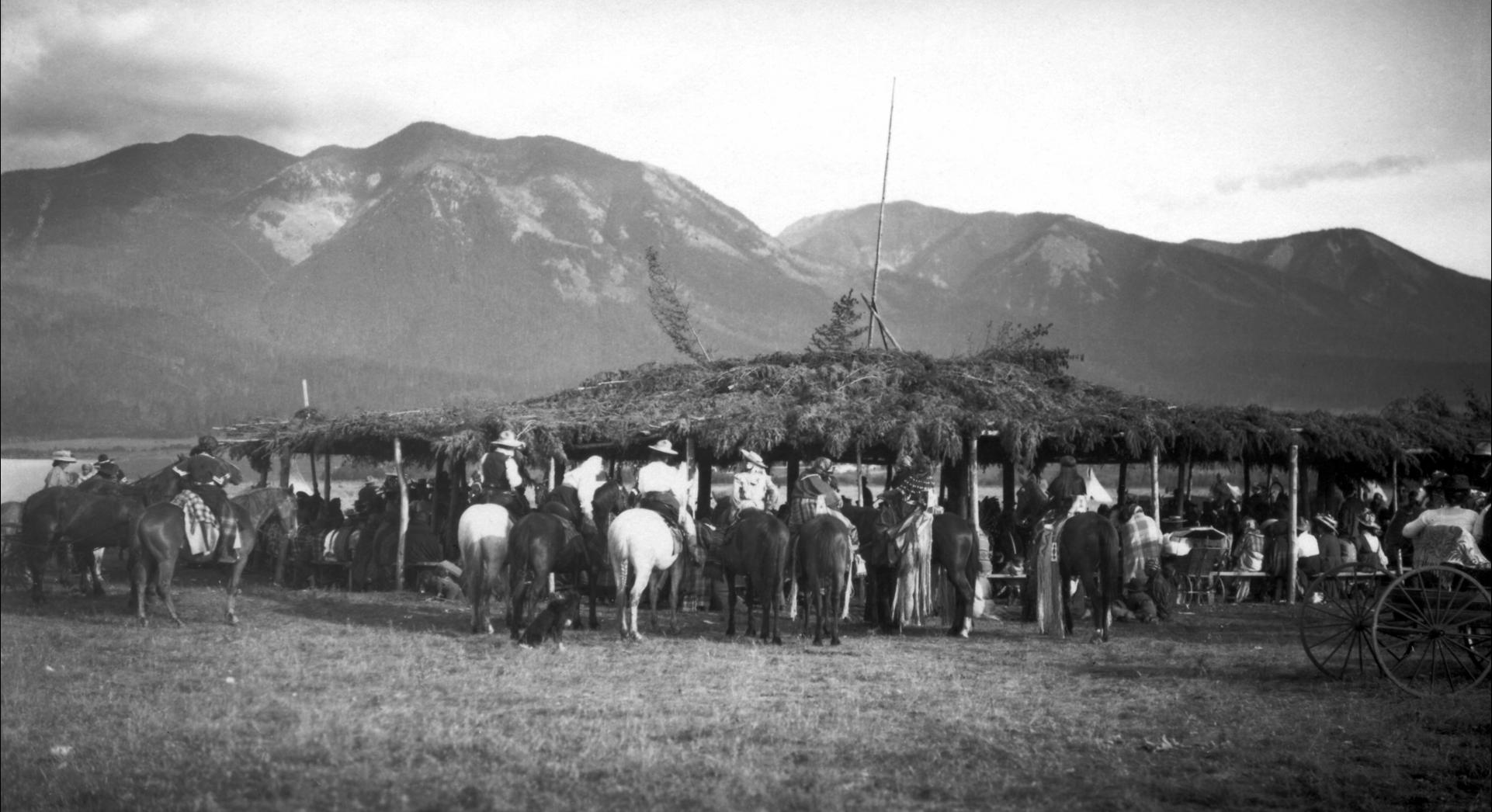

The Heart of the Monster is a landform that comprises the present day Jocko Valley in Arlee, Montana. The story, which has always been known in my community, goes that it is the remnant of a monster’s heart cast onto the mountain by Coyote (we don’t tell this story after winter so that’s all I can say at this time). In 2008, I was fortunate enough to have come across a piece of information from the older members of my community that hinted at an additional purpose of the landform, relating to river behaviour. The single sentence, documented in the 1950s, detailed that the heart could be seen when snow melted from its surface in the spring. When the snow was completely gone, it was thought that river flooding had ended.

Using this information, I recorded when the snow cleared and reconstructed the story from multiple sources. I correlated this data in a hydrology course in 2010 with river behaviour in relation to river crossing, and found that crossings tended to be safer when the Heart is fully visible. This is information that may have been used when my ancestors traveled to the eastern plains of Montana to predict potential danger along this journey, something that was vital to know. I update this data every year to track any further correlations or developments as it’s an ongoing research project.

Oral traditions of Indigenous people are a manifestation of what is believed to be the knowledge of a time before humans, when animals and now-extinct creatures contributed to the creation of landscapes and processes of the earth. This knowledge may be many generations removed from the world we live in, but it may hold information about processes that are still important today. These stories can provide a means to document and transmit many thousands of years of observation of a landscape – data sets from modern science reach back only hundreds of years. However, the manner of validation of these data can vary between modern science and the science traditions of Indigenous people. This variation can create mistrust and invalidate respective contributions. Indigenous and academic science communities have opportunities to find common ground on many fronts, including the exploration of the importance held in oral traditions as they relate to the human experience on the land and with each other.

Most stories that explain the landscape and animal features and behaviours are creation-type stories. The animals in these stories are often involved in unbecoming behaviour, so out of respect, the stories are only told in winter, when the animals are safely hibernating.

In the astronomical tradition of my community, there are fragments of knowledge related to constellations. Through my research, I promote a deeper look at what additional understandings may be held in traditions and stories from the past. One approach is my development of a story of a fictional event generated from fragments of actual events and common practices.

In brief, the story goes that the Salish people lived in the heart of the Rocky Mountains and made treks to the plains to hunt buffalo, a long and dangerous journey. It was the first time crossing the mountain for one young girl, and her family advised her to stay alert. That night at camp, the girl looked up to the clear night sky and watched čsp̓eʔl̓č̓s kʷkʷusm̓ (seven stars) as it traveled from east to west to note the time, just as her parents and grandparents had done.

The girl awoke to chaos – a band of enemies was raiding the camp. She fought but was captured and hit on the head. The last thing she remembered seeing was čsp̓eʔl̓č̓s kʷkʷusm̓ hovering between Sc̓altulexʷ (the place of the cold land) and Sč̓lxʷtin (the place where it is evening).

When she awoke, the horse she was tied to was at a slow trot. She looked in to the sky and saw čsp̓eʔl̓č̓s kʷkʷusm̓ nearly over the horizon in the direction of the Sc̓altulexʷ. From this and her knowledge of the stars in relation to time, she began to work on her escape, knowing she was not far from the last camping site.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation