Bacterial fingerprints in soil show where copper is buried

June 30, 2025

June 30, 2025

Researchers have identified buried copper ore by testing the DNA of microbes in the surface soil.

These ‘biological fingerprints’ can reveal copper-containing ore buried tens of metres below the earth’s surface without having to drill, according to new research in Geology.

“Copper is essential for clean energy technologies, including electric vehicles, and demand is skyrocketing,” said senior author Dr. Sean Crowe, professor in UBC’s departments of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences (EOAS) and microbiology and immunology. “Canada has almost 900 million tonnes of copper resources and potential for much more — but we need to find them first. This technology is another tool in the mineral discovery toolbox to improve our ability to find these critical resources.”

Current methods for mineral discovery are not necessarily sensitive enough, and can be subject to noise and false positives. The researchers hope that by combining the microbiological approach with current geochemical and geophysical methods, potential drilling options can be narrowed down to fewer sites and more exact locations.

When ore interacts with soil, it changes the communities of microbes there. The researchers tested this in the lab, introducing copper to soil microbes from two areas in Canada: tundra from the Northwest Territories, and a known porphyry copper deposit in Deerhorn, B.C. Sixty per cent of the world’s copper is mined from these kinds of deposits. The research team looked at how the microbes changed in number and species through DNA sequencing.

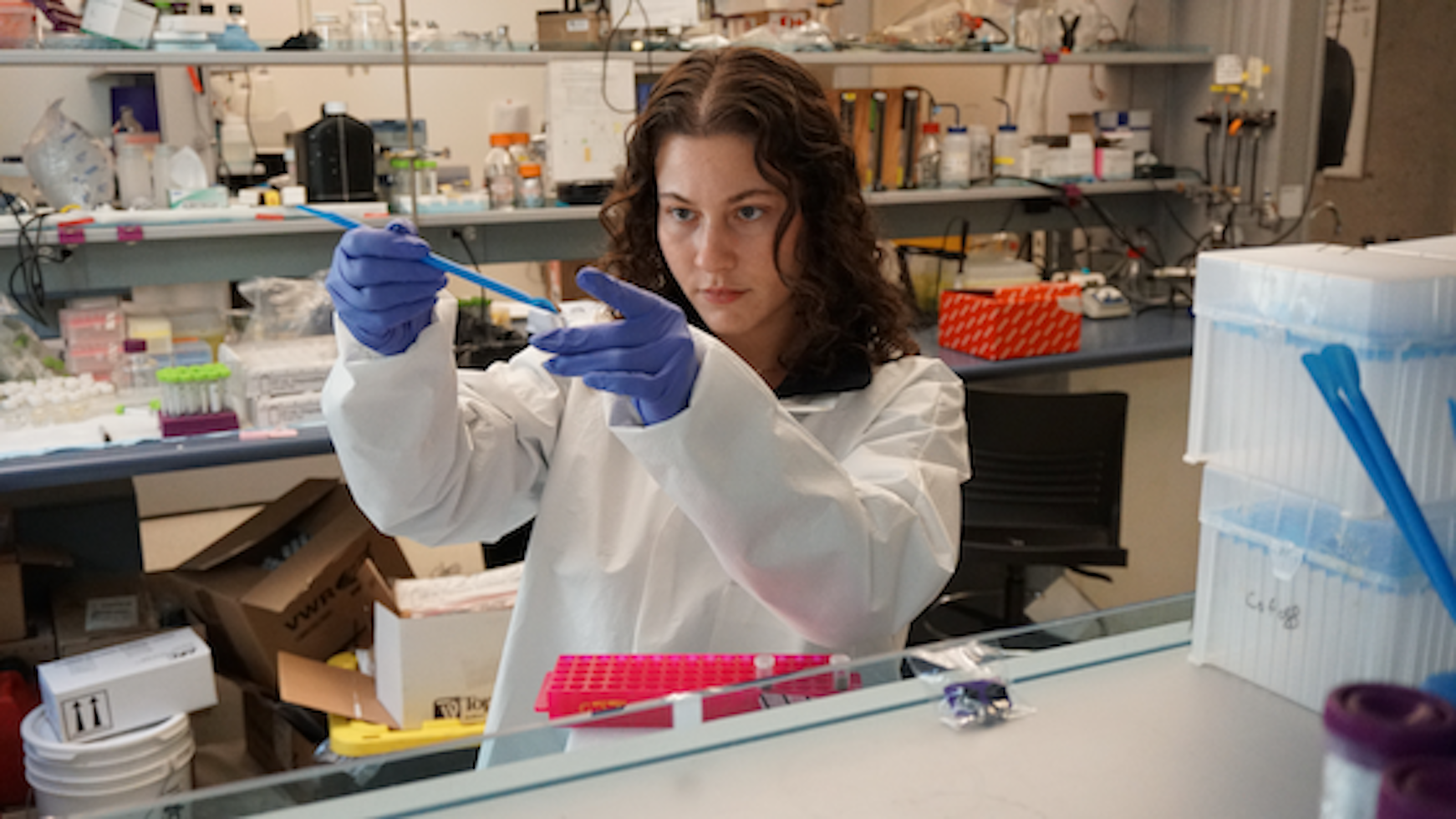

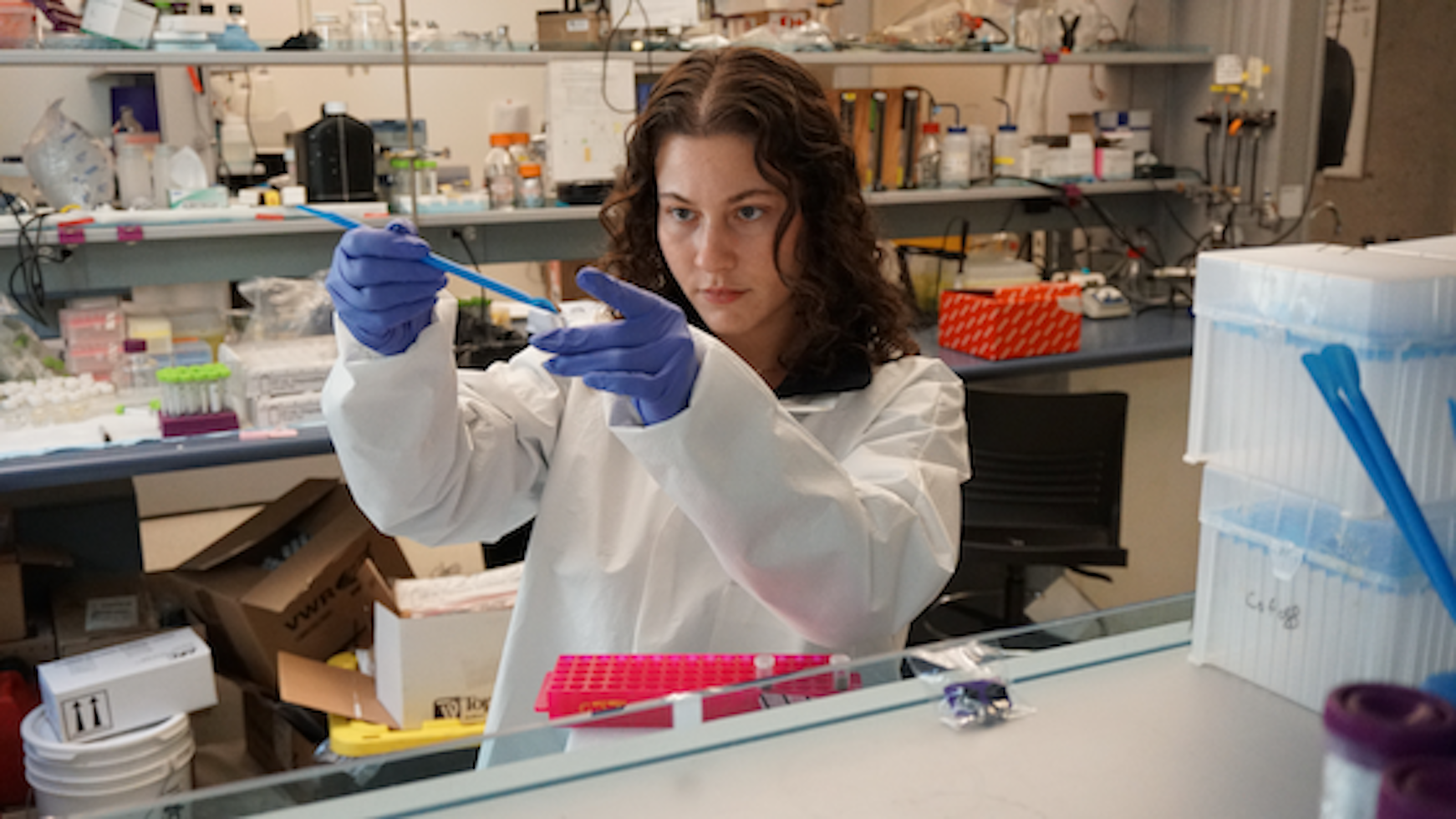

“We took those changed communities of microbes as indicators for the presence of copper—essentially a biological fingerprint made up of many individual species,” said first author Bianca Iulianella Phillips, a doctoral candidate in earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences (EOAS) and microbiology and immunology.

“We then analyzed the soil from Deerhorn, and found that from that fingerprint, 29 species of microbes are present above the mineral deposit. This demonstrates that there is a predictive capability with our technique, showing where copper deposits are buried.”

The team also found 66 new indicator species from the field site. Combined, the 71 bacterial fingerprints on the surface mapped topologically onto the copper deposit beneath.

The team first tried the technology with kimberlite, diamond-containing rock. In this new work, they investigated how far from the core of the mineral deposit indicator species could be detected. The team found they dropped off steeply more than 15 metres away from the rock, providing a tight radius for exploration.

This new application of DNA-sequencing technology shows the approach could be extended to other critical minerals. “Canada has significant undiscovered potential in a number of different commodities,” said Dr. Rachel Simister, a former postdoctoral fellow at UBC who worked on the project. “We are hopeful that techniques like microbial community fingerprinting can help increase Canada’s ability to provide new resources—such as nickel, zinc and gold.”

Discovery Genomics, a spin-off company that Dr. Crowe, Dr. Simister and Dr. Craig Hart are involved in, provides the specific expertise for these sequencing services at comparable costs to other discovery methods. With industry adoption, the technique could become cheaper, easier to use and someday, even portable.

“Our approach offers a new dimension to mineral exploration—enhancing discovery success and helping reduce costs with more precise targeting,” said Crowe. “As the industry adopts this approach more broadly, not only will it become more cost-effective and accessible, but the increasing volume of data will also make the technique more robust, accelerating learning and refinement.”

Currently, the research team is working with Geoscience BC, Teck Resources and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Alliance program to map the normal, or background, microbial communities in soils around B.C. and then analyze indicators from other porphyry copper deposits.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation