B.C. sea sponge has COVID-blocking powers

January 9, 2022

January 9, 2022

UBC researchers have identified three compounds that prevent COVID-19 infection in human cells, derived from natural sources including a B.C. sea sponge.

The discovery paves the way for the development of new medicines for COVID-19 variants made from natural sources. And given nature’s abundance, there could be a wealth of new antivirals waiting to be discovered.

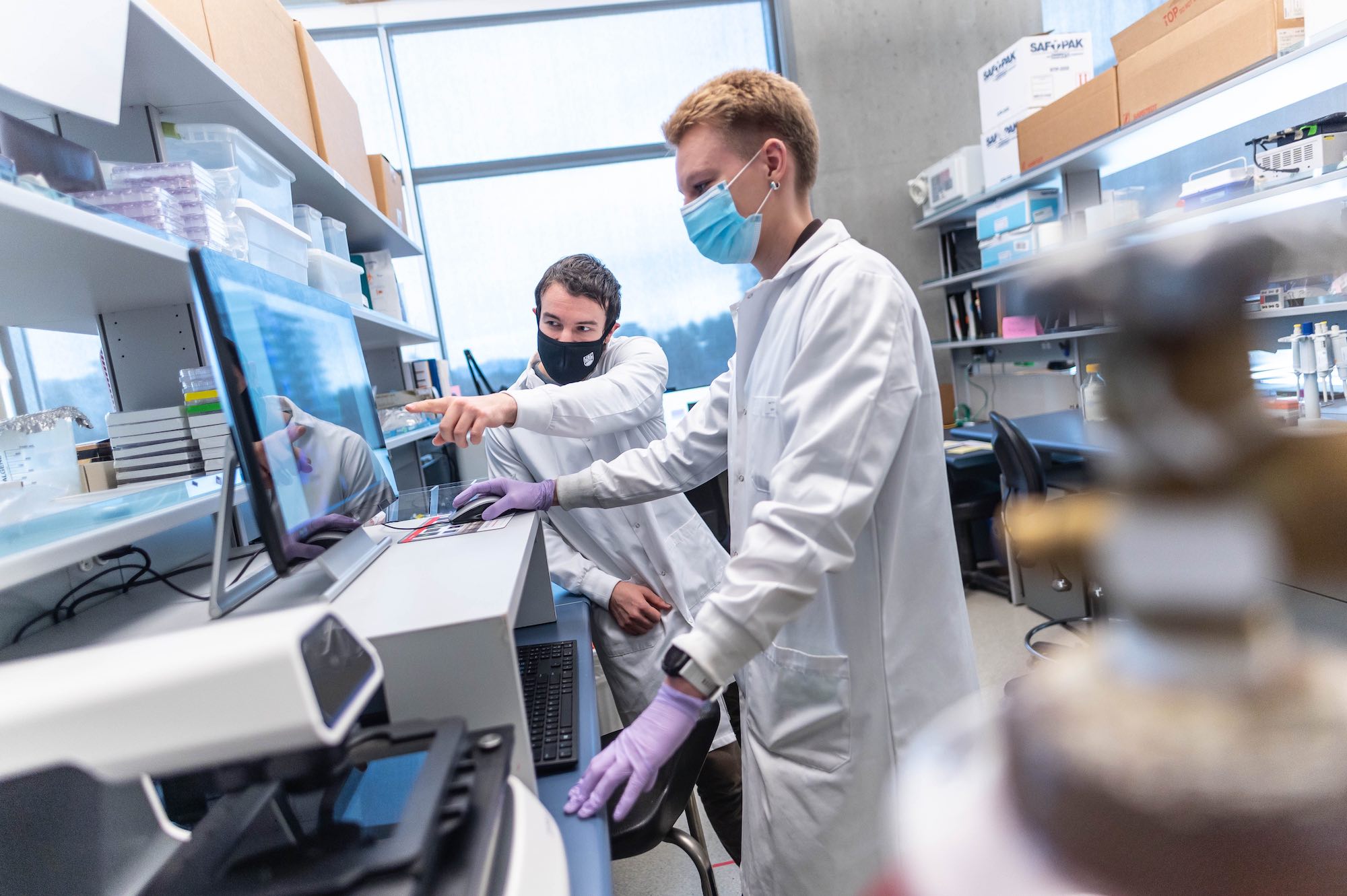

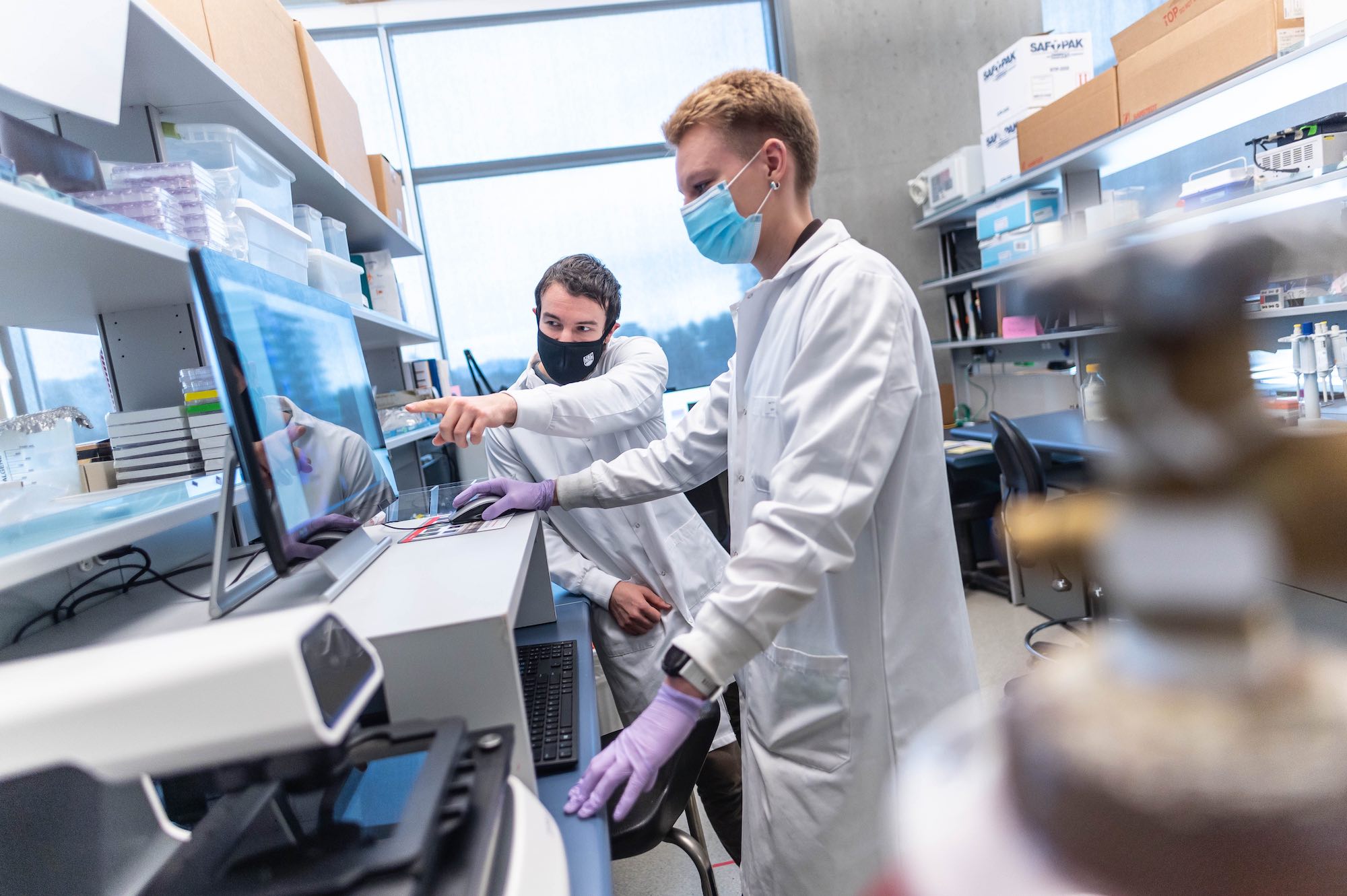

In a recent study, an international team of researchers led by UBC scientists investigated a catalogue of more than 350 compounds derived from natural sources including plants, fungi, and marine sponges in a bid to find new antiviral drugs that can be used to treat COVID-19 variants such as omicron. “This interdisciplinary research team is unraveling the important possibilities of biodiversity and natural resources and discovering nature-based solutions for global health challenges such as COVID-19,” said senior author Dr. François Jean, associate professor in the department of microbiology and immunology.

By bathing human lung cells in solutions made from these compounds and then infecting the cells with SARS-CoV-2, the researchers found 26 compounds that completely reduced viral infection in the cells. Three were effective in very small doses. “The advantage of these compounds is that they are targeting the cells, rather than the virus, blocking the virus from replicating and helping the cell to recover,” said co-first author Dr. Jimena Pérez-Vargas, a research associate in the department of microbiology and immunology. “Human cells evolve more slowly than viruses, so these compounds could work against future variants and other viruses such as influenza if they use the same mechanisms.”

The researchers used a version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes cells to glow fluorescent green when infected, as well as a special screening technique, to identify the top 26 natural compounds that showed inhibition of COVID-19 infection with low cell damage. The fluorescent virus is a powerful tool, said co-first author Dr. Tirosh Shapira, a postdoctoral fellow in the faculty of medicine. “With it, experimentally laborious steps are made redundant so we can easily and quickly check thousands of compounds. Even more important, with it we have the option to track SARS-CoV-2 'live' as it propagates from one cell to another.”

All three of the most effective compounds were found in Canada: alotaketal C from a sea sponge collected in Howe Sound, B.C., bafilomycin D from a marine bacteria collected in Barkley Sound, B.C., and holyrine A from marine bacteria collected in Newfoundland waters.

“We’ve been collecting things for 40 years all over the world, but these three just happen to be Canadian, and two are from B.C.,” said co-author Dr. Raymond Andersen, professor in the department of chemistry.

Further testing showed the three compounds were effective against the delta variant and several omicron variants, and they are about as safe for human cells as current COVID-19 treatments. Many of these treatments are no longer effective against currently circulating omicron variants because the virus is evolving. This highlights the need for new antivirals, said Dr. Jean.

The researchers explored how effective the compound bafilomycin D was when used in combination with a recently discovered COVID-19 antiviral, the molecule N-0385. They found the compound and molecule worked synergistically against the omicron subvariant BA.2. This suggests a promising starting point for developing multidrug treatments of omicron variants that are efficacious in treating COVID-19 and other viruses, said Dr. Jean.

The researchers plan to test the compounds in animal models within the next six months. “Our research is also paving the way for large-scale testing of natural product medicines that can block infection associated with other respiratory viruses of great concern in Canada and around the world, such as influenza A and RSV,” said Dr. Jean.

This research was funded by the Coronavirus Variants Rapid Response Network (CoVaRR-Net), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Genome BC, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Mitacs. Dr. Jean is lead, Pillar 10, Antiviral Strategies and Antiviral Therapeutics with CoVaRR-Net.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation