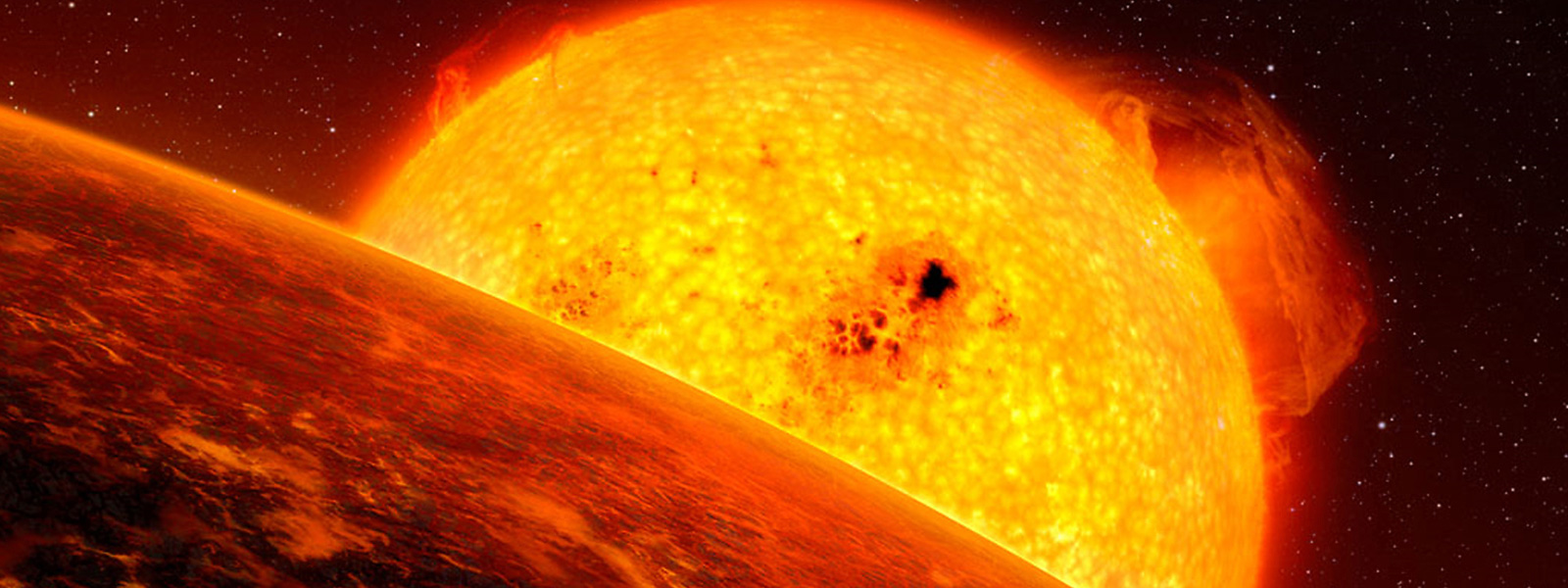

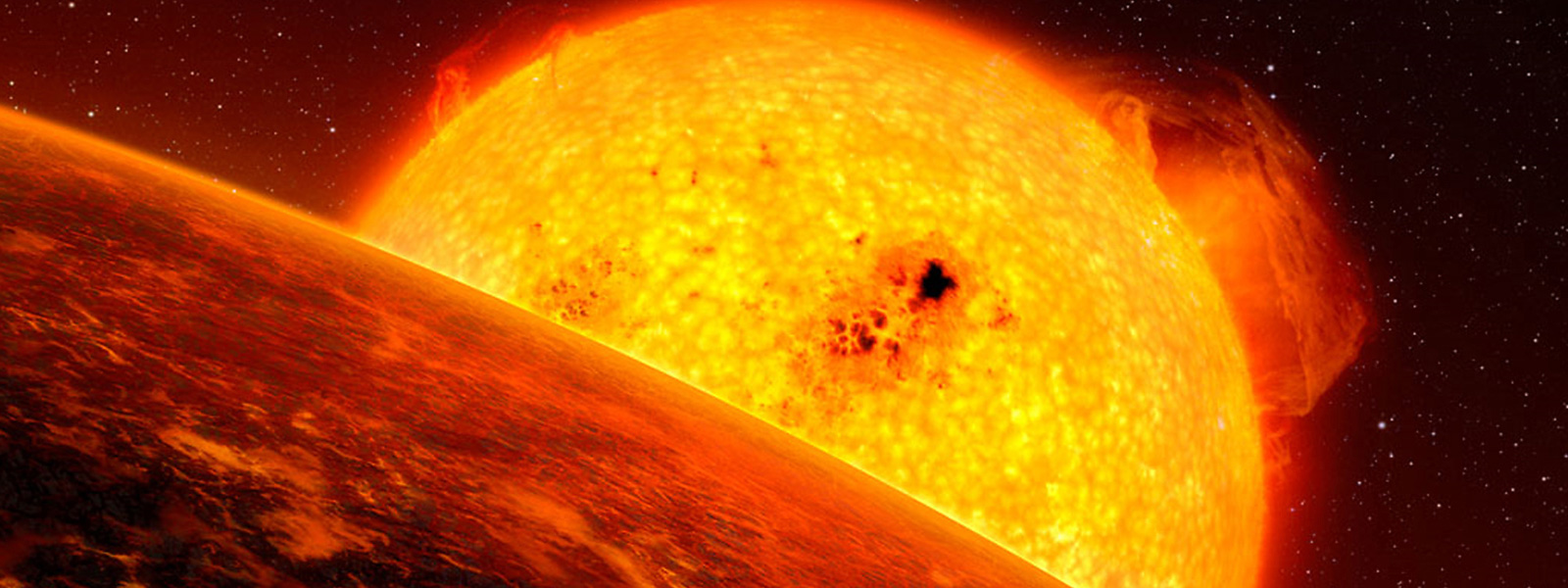

New way to measure a star's gravity could improve hunt for Earth-like planets

January 4, 2016

January 4, 2016

Astronomers from the University of British Columbia (UBC), Austria, Germany, France and Australia have introduced a new method to measure a star’s surface gravity – which depends on the star’s mass and diameter – to an accuracy of a few per cent.

The method—descibed in the journal Science Advances—will play an exciting role in the study of planets beyond our Solar System.

“If you don’t know the star, you don’t know the planet,” says study co-author UBC astronomer Jaymie Matthews. “The size of an exoplanet is measured relative to the size of its parent star. If you find a planet around a star that you think is Sun-like but is actually a giant, you may have fooled yourself into thinking you’ve found a habitable Earth-sized world.”

The new autocorrelation function timescale technique – or timescale technique for short – uses subtle variations in the brightness of a star’s pinpoint light recorded by satellites like Canada’s MOST and NASA’s Kepler (now K2) missions. The variations are caused by turbulence and vibrations in a star’s gas.

“When you cook soup on a stovetop, the soup rises to carry heat from the bottom of the pot to the surface, where some heat is lost to the air,” says the study’s lead author, Thomas Kallinger from the University of Vienna. “The liquid then sinks to pick up more heat and the cycle starts again.”

This circulation (known as convection) also occurs in gas near the surface of the Sun, and in most of the stars in the Galaxy. The convection and vibration cycles in the record of the star’s brightness across time (known as a light curve) have a characteristic timescale connected tightly to the star’s surface gravity.

Other methods to measure stellar surface gravity (spectroscopy, stellar seismology) work only for fairly bright stars with little noise in the data. The timescale technique can yield accurate results for faint stars even with relatively noisy light curves.

Future space satellites – the European Space Agency’s PLATO mission and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite – will need the best possible information about the stars they search to correctly characterise any planets they find.

The timescale technique is a simple but powerful tool that can be applied to the data from these searches to help understand the nature of stars like our Sun and to help find other planets like our Earth.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation