We still have a representation problem for women in physics – and Canada is no exception

April 25, 2025

April 25, 2025

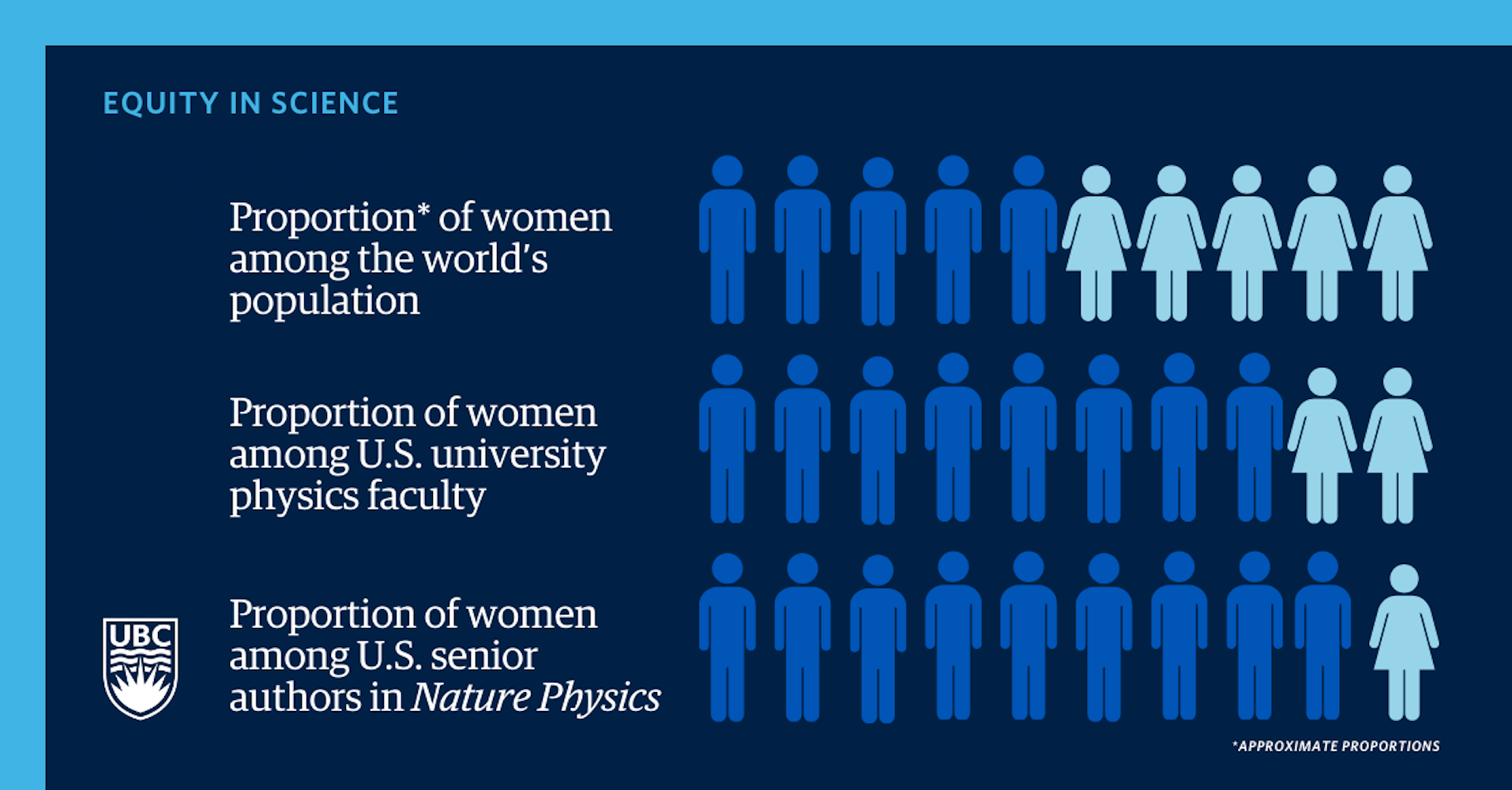

Fewer than one in 10 senior authors in a prestigious physics journal are women, according to a new study.

Of 15 countries, Canada has the worst record. The 33 Canadian-led papers in Nature Physics in the last 10 years had zero senior authors who were women, according to a new study published by the journal. Author Dr. Alannah Hallas, associate professor in the UBC Stewart Blusson Quantum Matter Institute and the department of physics and astrophysics, discusses the results and how they highlight the need for further support for young scientists in the field.

I was inspired to investigate this topic after speaking to a top scientific journal editor in 2019 who said while they didn’t collect data about representation of women authors in their journal, they were pretty sure it wasn’t a problem. I figured I’d check.

I looked at 1,804 papers published in Nature Physics from 2015 to 2024 where a senior author could be identified and assigned a gender based on the pronouns they used in their online profiles. I found that only eight per cent had a woman senior author. I was even more discouraged to find there wasn’t really any change with time—the situation is not getting better.

Canada had no women senior authors in the journal in the last decade. The U.S. had the highest number at 65, about 10 per cent of total U.S. senior authors in the journal. As of 2022, 18 per cent of physics faculty positions at U.S. universities were held by women. Canada doesn’t have comparable data, but in 2020, a self-reported census of the physics community found 29 per cent of professionals, including research staff and faculty, were women. So there’s a big gap between women physicists doing great work and women senior authors.

As I say in the paper, senior authorship is incredibly important for young researchers’ career progression. It’s a key determinant for who gets funding, awards and talk invitations. It tells your colleagues and the world, ‘This was my idea, I figured out how to solve this problem.’

The low number of senior women authors is a clear sign that there’s bias in the way we’re training young scientists. As a community, we need to tackle not just explicit bias, but the more insidious implicit bias. This can include how our community discusses young scholars’ work or suggestions of where to submit it: We all share preliminary findings at conferences or in the hallway at work, and negative or muted responses can feed into your perception of your work’s importance, so you don’t aim as high.

Firstly, the journal acknowledged the concerns highlighted and noted they started tracking the demographics of corresponding authors in 2023. In the paper, I highlight the need for more journals to audit their processes in order to understand why this low representation is occurring. Editorial teams could also offer networking events for young women scientists to establish relationships.

I was surprised to find Canada had no senior women authors. There is a mitigating factor in that we’re not a leading country in terms of the number of papers published overall—33 compared with 630 from the U.S. for instance—but any way you cut it, zero is a statistical outlier. Are there other factors that are making it more difficult for women physicists to thrive in Canada, such as excessive teaching or service burdens? It’s a tough nut to crack. I think some introspection is called for.

There’s no silver bullet for this. We need journals to play their part but we also need mentors, supervisors and our community at large to be conscious of the underrepresentation of women authors and to ensure these future research leaders are trained to believe in their work, and aim high.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation