New theory on how Earth’s subduction zones formed

August 28, 2018

August 28, 2018

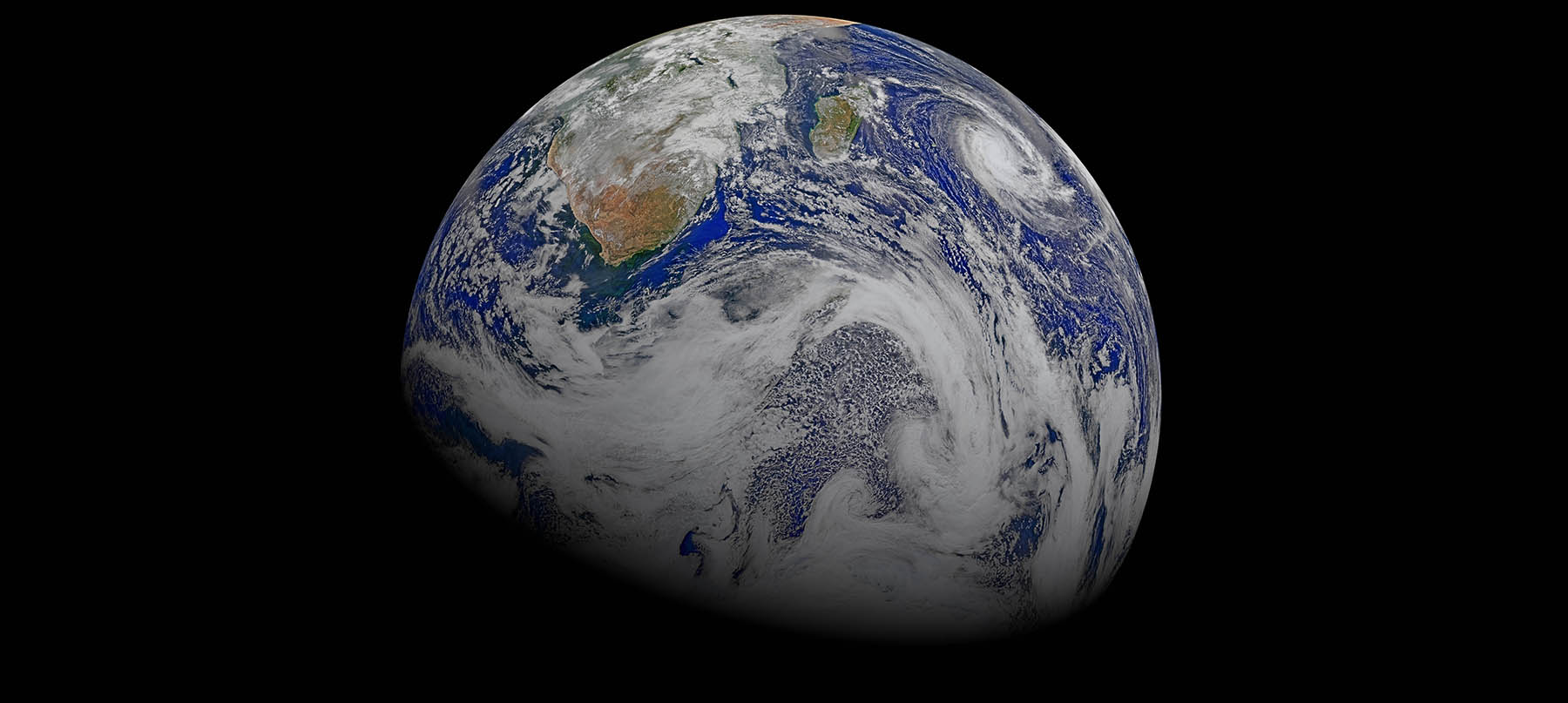

New research from scientists in Canada, the Netherlands, Norway and the UK indicates that some of Earth’s most active seismic zones were formed by plate tectonic changes elsewhere on the planet.

Previously, it was widely assumed that these fault zones—called subduction zones—formed spontaneously in a given location. The new theory could mean that changes in motion between two plates on one part of the globe could have unexpected effects elsewhere on Earth.

The work was published in Nature Geoscience.

The outer, rigid shell of Earth is broken into 60- to 200-kilometre thick tectonic plates that move along each other along large fault zones, causing most of Earth’s earthquakes. The most active of these plate boundaries are subduction zones, where one plate dives below another down into Earth’s interior. Once active, subduction zones can exist for tens or even hundreds of millions of years.

The widely accepted idea of how subduction zones form suggested that a piece of plate started to spontaneously sink into the mantle. This would create a gap at Earth's surface that becomes filled with magma, producing new, young crust. Only after millions of years would the sinking plate become heavy enough to start pulling adjacent plates together, creating horizontal plate motion and regular subduction.

“There are rocks on earth that we think formed in the early stages of a subduction zone. Some of these rocks are found in Oman, where most rocks formed by filling a gap with new crust next to a new subduction zone, and some formed right at the subduction interface,” said the study’s lead author Carl Guilmette of Laval University, Quebec. “Previously, we could only date when the rocks of the new crust formed and assumed that this occurred simultaneously with the first formation of a subduction zone.”

Matthijs Smit, a dating specialist at the University of British Columbia and co-author of the study, managed to also date the formation of the rocks at the subduction interface. “We show that they are at least eight million years older than the age of the crust that filled the gap. This means that horizontal plate motion came first, and the formation of the gap came later as a result, and not as a cause, of subduction.”

The new result has major implications for our understanding of plate tectonics.

“For the first time, we unequivocally demonstrate that subduction zones form because of changes in plate motion elsewhere,” says Douwe van Hinsbergen, an author from Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “Focus of follow-up research is now on which processes exactly drove the formation of the subduction zone that existed in Oman, but we may be searching across the planet.”

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation