A digestive ‘treasure chest’ shows promise for targeted drug treatment in the gut

May 1, 2025

May 1, 2025

A new approach to drug design can deliver medicine directly to the gut in mice at significantly lower doses than current inflammatory bowel disease treatments.

The proof-of-concept study, published today in Science, introduced a mechanism called ‘GlycoCaging’ that releases medicine exclusively to the lower gut at doses up to 10 times lower than current therapies.

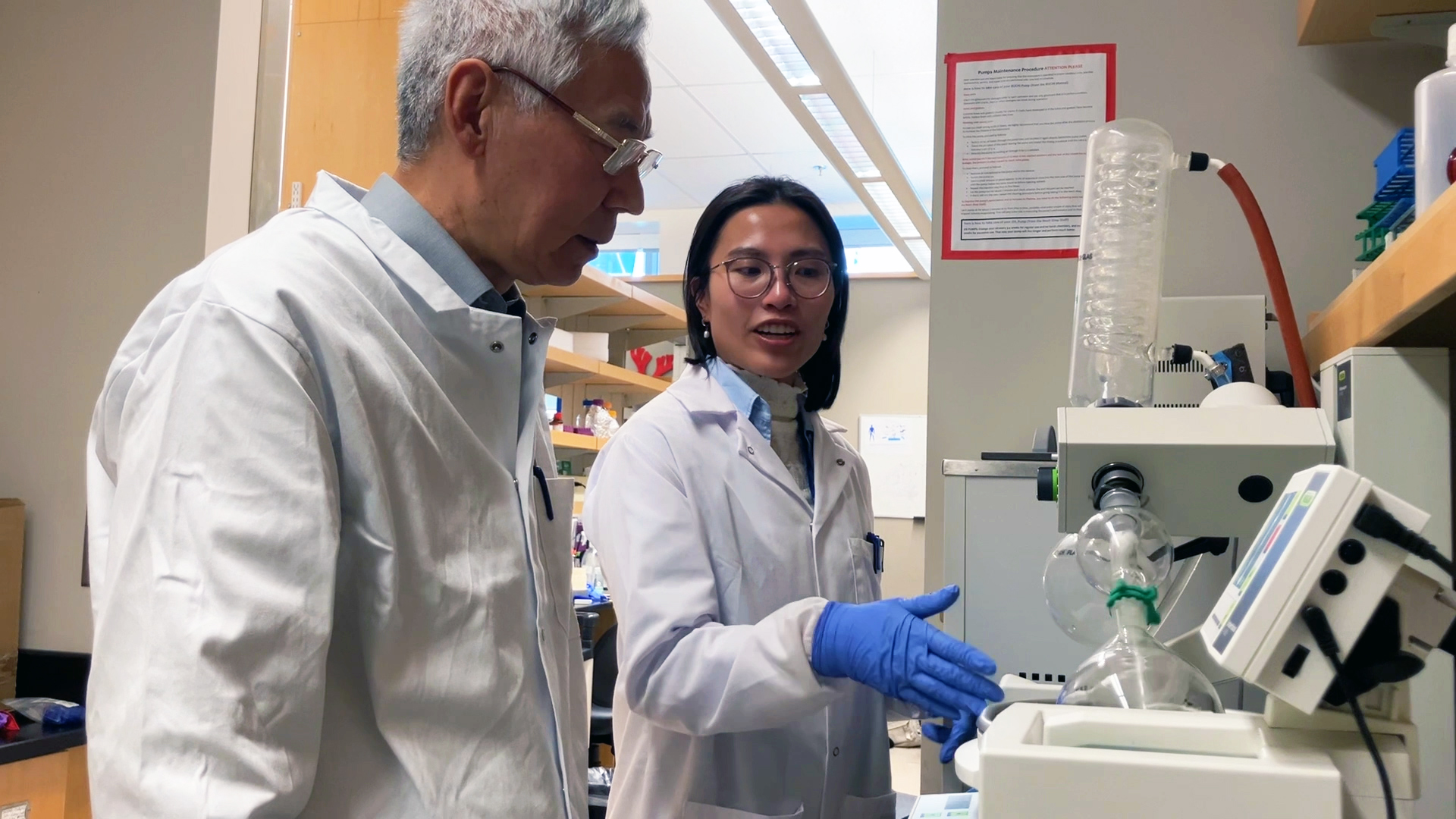

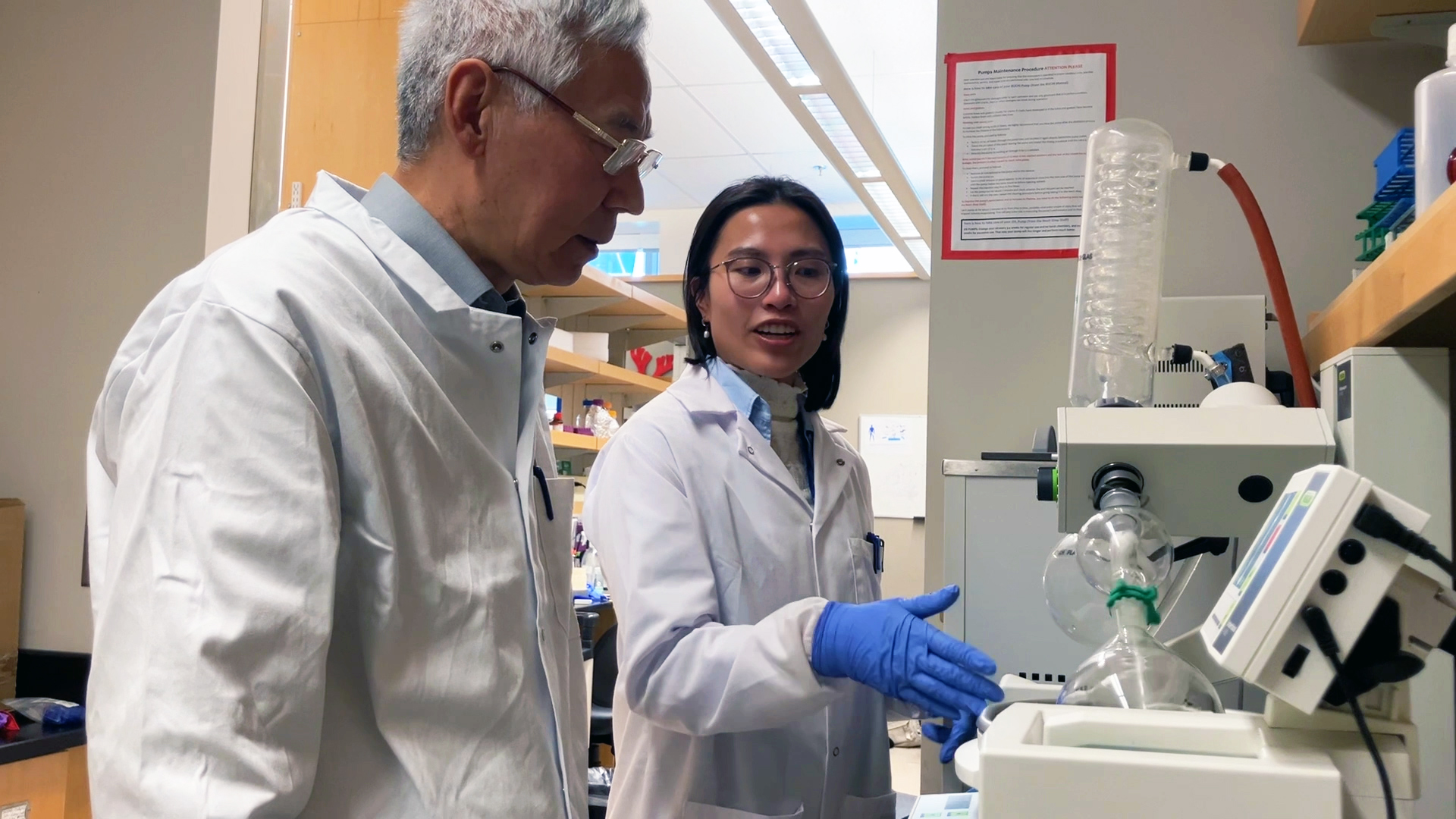

“With this technique, we have the ability to deliver not just steroids, but a range of drugs including anti-microbial compounds directly to the gut, potentially helping people with inflammatory bowel disease, gut infections and more,” said co-senior author Dr. Harry Brumer, a professor in the UBC department of chemistry and Michael Smith Laboratories (MSL).

An estimated 322,600 Canadians have inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as of 2023 and Canada has one of the highest incidence rates in the world, according to Crohn’s and Colitis Canada.

“It’s a growing problem, and there’s no known cure. It can be completely debilitating and it hits people in the prime of their life, between 19 and 29 years of age,” said co-senior author Dr. Laura Sly, professor in the UBC department of pediatrics.

One of the treatments for IBD is anti-inflammatory steroids, often taken orally or intravenously. These have serious side effects including osteoporosis, high blood pressure, diabetes and negative mental health outcomes. They are used to treat flares for children, adults, and the roughly 30 per cent of adults for whom treatment with other medication doesn’t work.

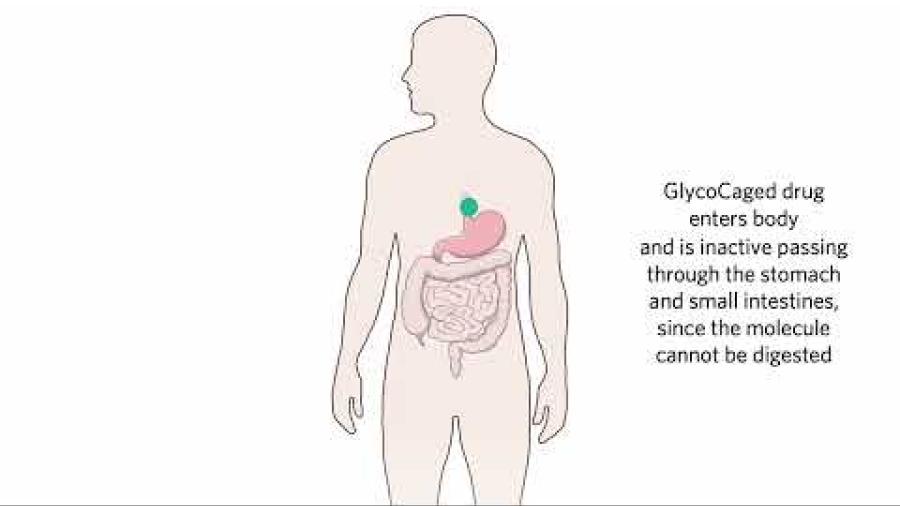

Much of the medicine is absorbed in the stomach and upper intestine before reaching the inflamed gut area, so doctors administer the potent drugs in high doses to ensure an effective amount reaches the affected areas.

GlycoCaging is a chemical process inspired by the UBC researchers’ realization that certain molecules found in fruit and vegetable fiber can only be digested by bacteria that resides in our gut.

The team bonded the molecule to a steroid, creating a ‘treasure chest’ for which the ‘key’ is a specific gut bacteria. They used a steroid not usual for IBD treatment to demonstrate GlycoCaging’s potential to repurpose potent drugs.

Using this mechanism, the researchers treated two types of mice that had IBD for up to nine weeks. Their GlycoCaged doses were three to 10 times lower than non-caged doses but had the same anti-inflammatory effects. The drug turned up in lower levels in the rest of the body than the non-caged version. In one group, inflammation in other areas of the body was not reduced, meaning the drug indeed affected only the gut.

“We showed that this technique can be used on other steroids, including those commonly used in IBD treatment, as well as other anti-inflammatory drugs used in high doses with negative side effects,” said Dr. Changqing Wang, research associate in UBC department of chemistry and MSL.

To test the potential for treatment in humans, the research team checked to see if the bacteria upon which GlycoCaging relies existed in the gut of those with IBD.

They looked for bacterial activity in fecal samples from 33 people, with and without IBD, and at a global database for genetic markers. “We found that all people in the fecal sample study had the ability to activate the drugs, including people with IBD whether they are in remission or have active inflammation,” said Maggie (Wei Jen) Ma, a doctoral student in UBC’s experimental medicine program and BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute. “And, the majority of people had genetic markers indicating the ability to use the GlycoCage system.”

The research team has patented the technology and will now source funding for more advanced animal trials and human clinical trials.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation