How a common virus might trigger multiple sclerosis

February 23, 2018

February 23, 2018

UBC immunologist Marc Steven Horwitz investigates how viruses can induce complex diseases like diabetes and lupus. Now he’s studying a cat and mouse game—how a common virus might be related to the onset of multiple sclerosis (MS).

What is Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and how common is it?

Epstein-Barr is the virus that causes mononucleosis, aka ‘mono.’ It's also called the ‘kissing disease’ because it’s spread via saliva. About 95 per cent of all adults worldwide have been infected with EBV.

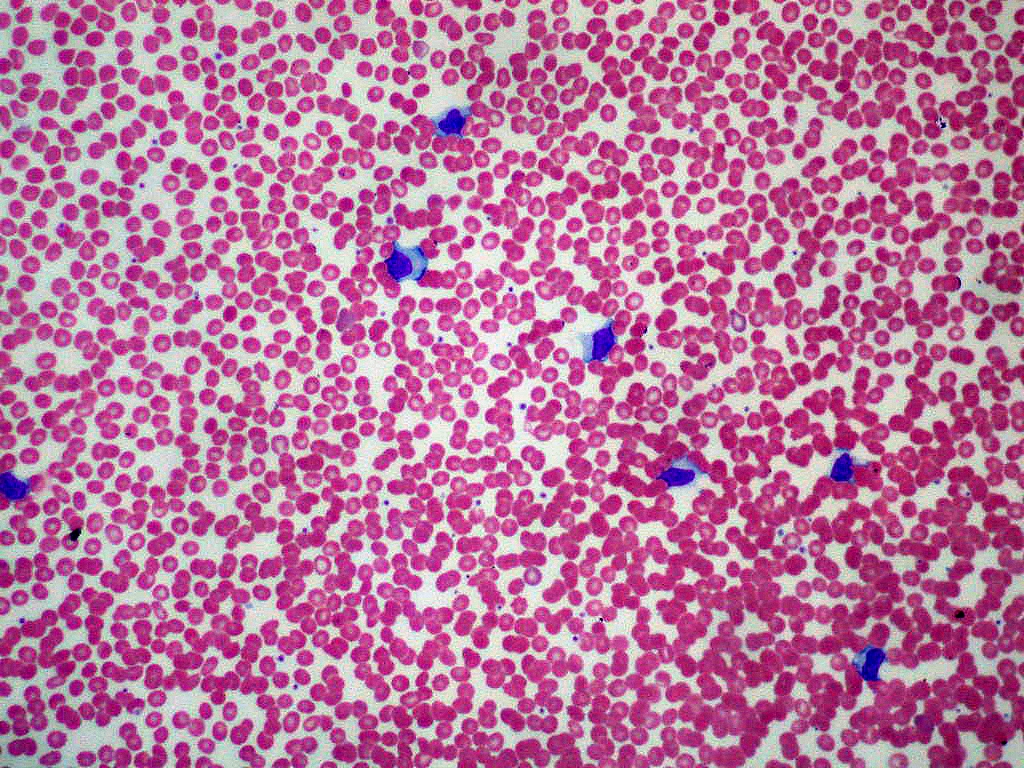

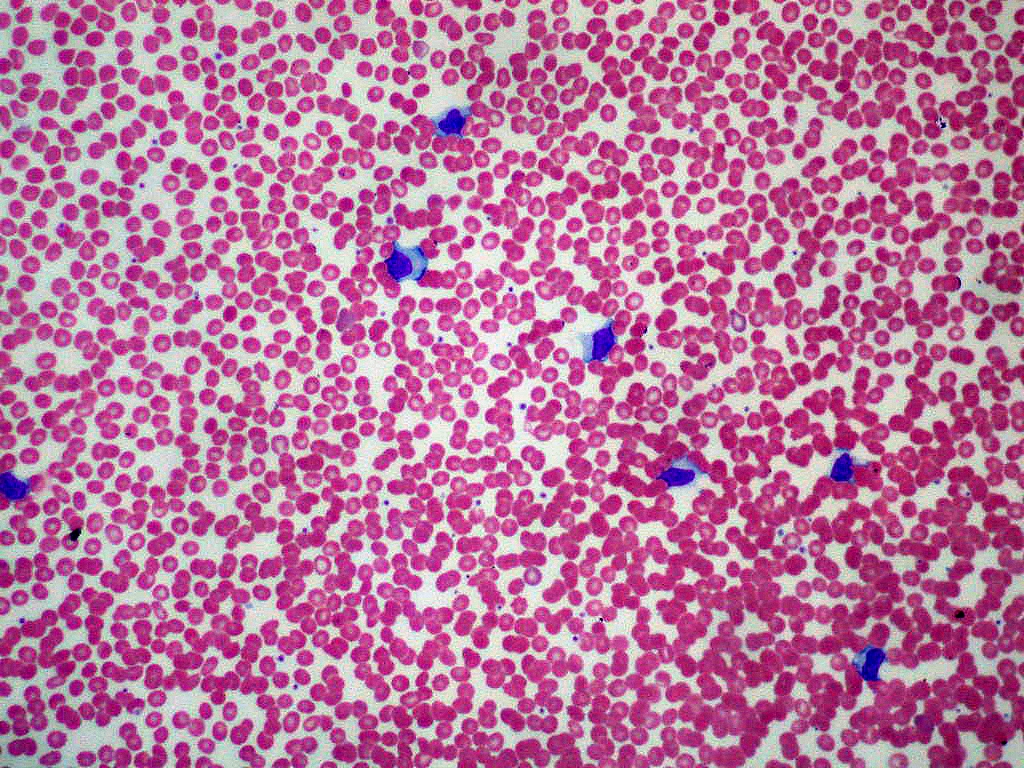

EBV stays in your body after infection. This isn’t unusual – the herpes virus stays in our neurons, for example. But in the case of EBV it lays dormant in memory B cells and manipulates the immune system to remain there.

What’s the link between EBV and MS?

Historically, EBV infection has been associated with the development of several autoimmune diseases and cancers. MS patients have increased levels of antibodies against EBV. When you look at children with MS, all of them have been exposed to EBV, but only 40 per cent of healthy kids have EBV.

Think of a cat and a mouse. The virus is the mouse and the cat is your immune system. The mouse is hiding in a mouse hole. The cat can’t see it, but it can smell it and it’s ready to attack. If you put your hand between the cat and the mouse hole, chances are the cat is going to attack you. We believe this is what happens in your body. Some factor suddenly triggers the ‘cat’ immune system and your body has a reaction which leads to MS.

EBV is a herpes virus and humans have evolved with the family of herpes viruses. At some point, EBV might have helped protect us from another pathogen. Maybe the way we interact with the virus has changed and that’s the problem.

What are the practical applications of your research?

It turns out that drugs that help patients with MS affect the EBV present in the body. We believe that eliminating or reducing the presence of the virus might assist patients with MS, diminishing their relapses. But we still don’t understand how EBV might cause MS. By studying the role EBV plays in the progression of MS, we could develop better therapies for patients. There is also a need for a vaccine, as EBV is also the cause of several cancers.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation