An international team of astronomers—including scientists from UBC Physics and Astronomy and the University of Toronto—have unveiled the birthplaces of ancient stars using a two-tonne telescope carried aloft by a 33-storey high balloon.

After two years analyzing data from the Balloon-borne Large-Aperture Sub-millimeter Telescope (BLAST) project, astronomers and astrophysicists from Canada, the U.S., Europe, Mexico and South America revealed today that half of the starlight of the Universe comes from young, star-forming galaxies several billion light years away.

"The history of star formation in the universe is written out in our data. It is beautiful. And it is just a taste of things to come," says Professor Mark Halpern, part of the UBC team that also includes Professor Douglas Scott and post-doctoral fellows Ed Chapin and Gaelen Marsden.

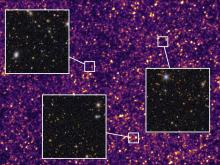

"Over the last decade, submillimetre telescopes on the ground have produced several 'black and white' images no larger than the size of a fingernail at the end of your outstretched arm," says Chapin. "In a single 11-day flight BLAST has taken a huge leap forward, producing colour images the size of your hand."

The results were published this week in Nature.

In the 1990s, NASA's COBE satellite discovered a nearly uniform glow of submillimetre light, known as the Far Infrared Background. It had been expected that this radiation was coming from warmed dust enshrouding bright young stars, but the nature of the galaxies which contain the dust had remained a mystery.

The Nature study combines BLAST submillimetre observations at wavelengths around 0.3 mm--between infrared and microwave–with data at much shorter infrared wavelengths from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope to confirm that all of the Far Infrared Background comes from individual distant galaxies, answering a decade-old question of the radiation's origin.

"While those familiar optical images of the night sky contain many fascinating and beautiful objects, they are missing half of the picture in describing the cosmic history of star formation," says Scott.

"Stars are born in clouds of gas and dust," says Barth Netterfield, a cosmologist in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at U of T. "The dust absorbs the starlight, hiding the young stars from view. The brightest stars in the Universe are also the shortest lived and many never leave their stellar nursery. However, the warmed dust emits light at far-infrared and submillimetre wavelengths – invisible to the human eye, but visible to the sensitive thermo-detectors on BLAST."

In addition to leading the data analysis, the Canadian scientists also constructed much of the hardware that made BLAST a reality. The aluminum gondola was designed to protect the telescope, the onboard computers and data upon landing. The motorized pointing system controlled the 2,000 kilogram payload with its two-metre-in-diameter telescope--the largest of its kind--to one one-hundredth of a degree in precision.

The complex electronics monitored and recorded nearly 1,000 sensors while the software--nearly 300,000 lines of code–controlled the payload during its long flight 39 kilometres above the Earth. Flying the telescope above much of the atmosphere allowed the BLAST team to peer out into the distant Universe at wavelengths nearly unattainable from the ground, and uncover dust-enshrouded galaxies that hide about half of the starlight in the Universe.

"BLAST has given us a new view of the Universe," says Netterfield, whose U of T colleagues on the project include department chair Peter G. Martin and graduate students Marco P. Viero, Donald V. Wiebe (now a post-doc at UBC) and Enzo Pascale (now a faculty member at Cardiff University). "The data we collected enable us to make discoveries in topics ranging from the formation of stars to the evolution of distant galaxies."

BLAST is also uniquely capable of studying the earliest stages of star formation locally, in the Milky Way Galaxy. The BLAST collaboration is also releasing a study, submitted to the Astrophysical Journal, of the largest survey to date of the earliest stages of star formation. This study documents the existence of a large population of cold clouds of gas and dust, many of which have cooled to less than -260 C. These cold cores, which exist for millions of years, are the birthplaces of stars.

The BLAST team includes contributors from the University of Pennsylvania, the University of British Columbia, the University of Toronto, Cardiff University, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Brown University, Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Astrofısica Optica y Electronica, the University of Miami, the University of Puerto Rico, and France's Laboratoire APC.

The BLAST experiment has been supported by funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs, the Canadian Space Agency, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council, and with assistance from Benjamin Magnelli, WestGrid computing resources and the SIMBAD and NASA/IPAC databases, the Columbia Scientific Balloon Facility, Ken Borek Air Ltd., and the mountaineers of McMurdo Station, Antarctica.

Musqueam First Nation land acknowledegement

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation

Faculty of Science

Office of the Dean, Earth Sciences Building2178–2207 Main Mall

Vancouver, BC Canada

V6T 1Z4