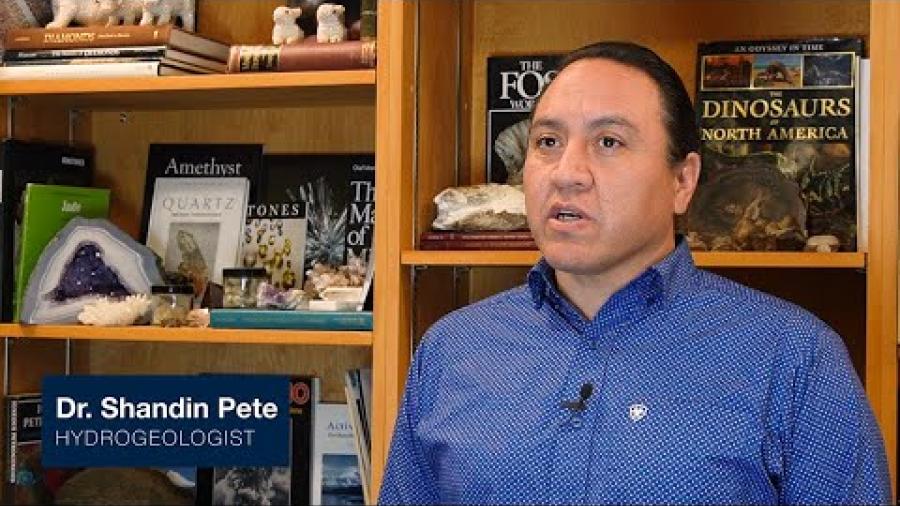

When Dr. Shandin Pete joined the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) in 2021, it presented an opportunity to bring Indigenous perspectives to UBC Science.

Dr. Pete, who is Salish and Diné, completed a PhD in geoscience at the University of Montana, prior to obtaining a Ed.D. from that institution. Over the past decade, he has taught at Salish Kootenai College in Montana where he established an Indigenous Research Center, and conducted research in a range of Earth Science domains exploring connections between Western Science and Indigenous Knowledge to promote the sustainable use of water and mineral resources.

Here at UBC, he is involved with three projects funded through the university’s Indigenous Strategic Initiative Fund.

In this edited conversation Dr. Pete discusses the groundswell in academia to acknowledge the value of Indigenous knowledge and some of the challenges of integrating it with Western science.

EOAS is very open to trying to figure out how an Indigenous understanding of the world can be situated in the geosciences. Of course, there's a question of how it gets done. Everybody's stuck at that stage. It’s a difficult puzzle to solve. Even Indigenous scholars are saying, we don't know how to inform a non-Indigenous person how to introduce an Indigenous way of knowing in a topic that may be foreign to us, ourselves, and also to an audience that's largely non-Indigenous.

It's going to take hiring more Indigenous faculty with the experience to understand the value of their own ceremonial and traditional life, who have also navigated the academic structure that's required to achieve faculty positions. It would be awesome to have Indigenous colleagues that can understand so we don’t have to do so much back work to fill people in on certain things. By reaching a critical mass of those kinds of people we can deconstruct the phenomenon of how a knowledge system which does not operate and is not generated in academic space can find a place at UBC. Right now, it's a mystery to my non-Indigenous colleagues and it is equally mysterious—not in the same way—to my Indigenous colleagues as well.

To attract young Indigenous people to university there has to be an opportunity to perform inquiry that's familiar to students. That's not just Indigenous students, but people of all backgrounds. I think there's a natural human inquisitiveness that can often be murdered by institutions through a method of teaching that doesn't quite align with the way the mind wants to learn. So to learn about any first year topic, you get pummeled for 13 weeks with lecture after lecture and memorization. There's a certain degree of that that needs to occur, but I think there are more transformative ways to engage the human mind to allow people to think and discover things on their own.

Field schools should be the first experience students have so they can engage in activities that emulate what they might be doing in a future profession. That gets people excited. It shows you what the potential is.

Indigenous knowledge systems and structures can be transmitted in a written form, but I think there has to be a certain level of caution taken when doing that because it makes that things static, very locked into time and place. I saw that in my own community, the Flathead Indian Reservation in Arlee, Montana, where young learners were curious about cultural traditions that they weren't raised with. They'll pick up a book and it's situated in the past, or it's been translated and censored and reconfigured to meet a certain type of audience today.

Our oral traditions are now often in books but they've been edited and re-edited for children so we don't get the complete story. We get the Disney version. They've been turned into fables. When young people read that, it becomes sort of like a law, something that is perpetual going forward and backward in time, without understanding that the ideas of our own tradition are very fluid and transient. They meet the need of whatever is occurring at the time. That's the danger when we when we commit some of the Indigenous knowledge to writing.

My criticism of current Indigenous academic pursuits is that they need a disclaimer saying this is a snapshot in time and it shouldn't be broadly applied, both temporally and spatially, across the Indigenous sphere. The modern Indigenous scholar has to locate the original stories or recordings from the early 1900s and try to glean information from what was told at that time. But we can’t take anthropological records from long ago at face value. You have to filter out what’s meaningful.

Our ceremonial traditions are the pathway to re-access Indigenous science. That's difficult for Western science to grasp because we don't keep a field book about it or publish a paper saying this is how we understood things.

My pursuit and my passion is reclaiming traditions among my own people. I find any instance I can to augment the values that were found in our code of morality, that lead us to understanding more about the traditions and values of our older people. Most of the time that includes something about the landscape. We were inherently tied to the landscape, because that was our means of survival. A lot of the understanding and the knowledge, any sort of data input, always came from the landscape. Processes such as the hydrological cycle were inherently important to many things related not only to domestic affairs, but to spiritual affairs as well.

So something as simple as understanding snow melt on the mountains. Why was that important? Well, we find out that it's connected to a spiritual tradition. But it's also connected inherently to a more domestic tradition, which is travel across the landscape. So through some of my archival research I happened to come across a small sentence that indicated there's a marker that was related to something about river behavior. That became a research project I engaged in with students at the tribal college to monitor when snow melted off of an important feature associated with a creation story, and then associate that with river discharge at locations along a buffalo hunting trail.

And I think it ties them to many other markers that indicated when the buffalo in the eastern part of Montana were ready to be hunted, because our main food base, at least early in the 1800s, was the bison. It was also an indication of when the trails became passable because you had to cross rivers. You don't want to get there too soon or the river is still flooding and you have to wait until it recedes so you can wade across. What that means today, I don't know. We don't do that anymore. But it's interesting. It ties the past to some present hydrological phenomena.