UBC seahorse expert wins world’s top animal conservation award

May 12, 2020

May 12, 2020

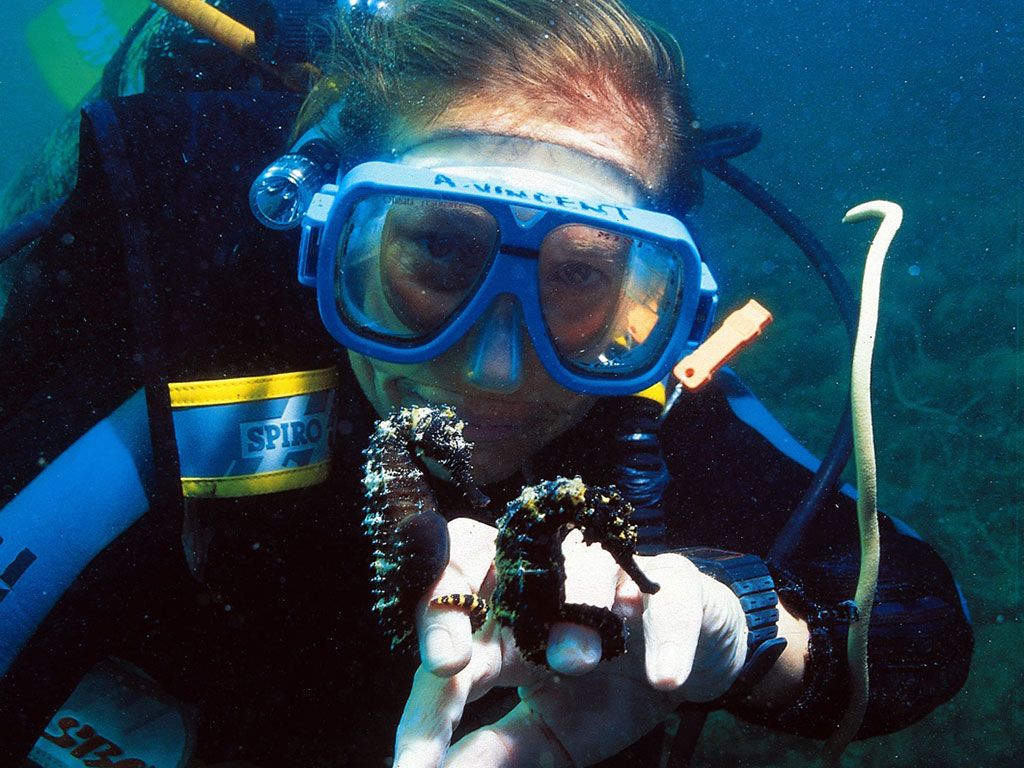

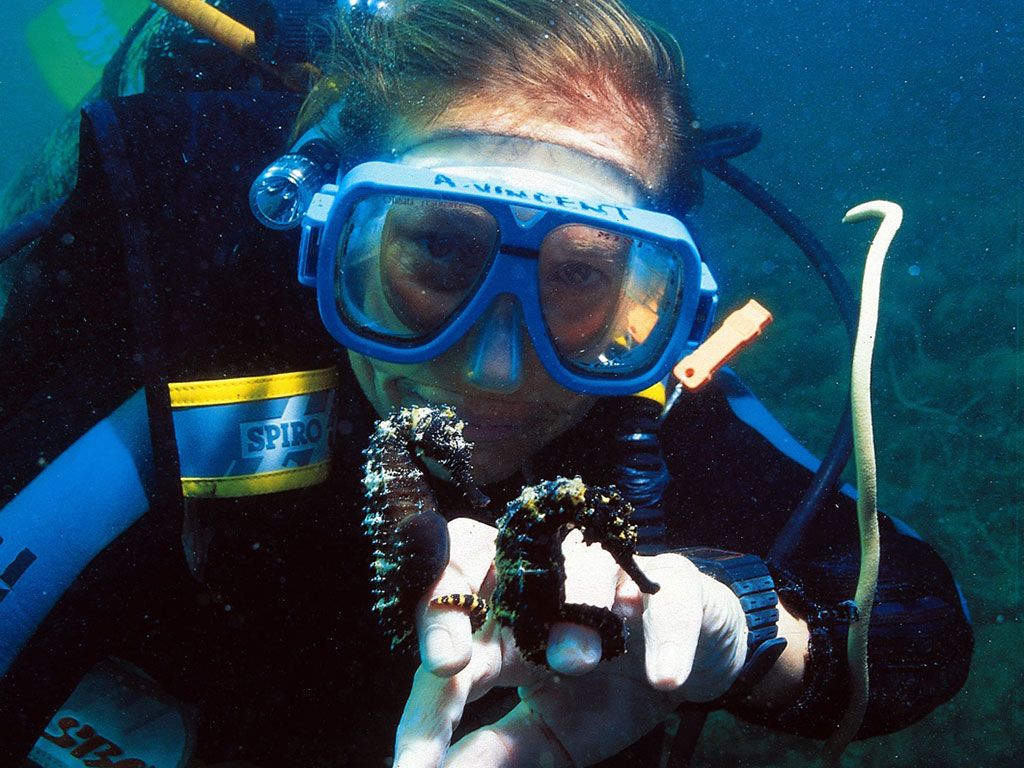

University of British Columbia marine biologist Amanda Vincent has won the 2020 Indianapolis Prize, the world’s foremost award for animal conservation, for her trailblazing work to protect seahorses and other marine life.

The influential prize recognizes conservationists who have made significant progress in saving a species, or multiple species, from extinction. Vincent, who was the first biologist to study seahorses in the wild, has dedicated her career to investigating their ecology, uncovering their extensive global trade and establishing projects for their conservation around the world.

“I’m absolutely thrilled. The Indianapolis Prize is as close as one gets to a Nobel Prize in animal conservation,” said Vincent, a professor at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at UBC, where she directs Project Seahorse. “I started off wanting to save seahorses but we quickly realized that many of the biggest threats to seahorses – from illegal wildlife trade to annihilation fishing practices like bottom trawling – are the same threats faced by many other ocean species and habitats. If we could convince people to protect seahorses, maybe we could save the ocean too.”

Vincent’s work has not only brought attention to seahorses but has also helped develop effective approaches to conservation that have improved the status of many other marine fishes, such as sharks and rays, and protected vast swathes of coastal habitat across the world.

“Amanda Vincent’s determination to protect the ocean and the species that inhabit it is nothing short of heroic,” said Rob Shumaker, president and CEO of the Indianapolis Zoological Society Inc., which presents the award every other year. “Vincent brings a collaborative, culturally sensitive and solutions-focused approach to ocean conservation that inspires and drives positive outcomes for marine species. It’s our privilege to recognize and reward her for her immeasurable impact on ocean conservation and future of seahorses around the world.”

Vincent’s pioneering approach to their conservation rests on three pillars: a deep knowledge of the animals, promotion of the fish as essential to the world’s biodiversity and collaborative, sustainable management approaches that also benefit humans.

Vincent is the foremost expert on their biology, having studied them in 38 countries and co-authored a definitive taxonomy that helps distinguish between the 44 look-alike species.

“My interest in them began as a way to study the evolution of sex differences because only male seahorses get pregnant and give birth,” said Vincent, who discovered that some species form monogamous pair bonds.

But it was a chance sighting of a billboard in Germany advertising seahorses from the Philippines as a good for “men with weak tails” that marked a profound shift from scholarship to action in the early 90s.

“I spent the next few years doing detective work through Asia and eventually managed to map out this massive hidden trade in seahorses spanning about 80 countries,” said Vincent. “The scale of the trade was astounding, with millions of seahorses being sold for use in things like traditional medicines, aquarium displays and souvenirs.”

Vincent realized that in order to protect them, she needed to get them recognized as something other than simply a resource for exploitation – both at global and local scales.

So in 1996, she led the global conservation community to include seahorses on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List – the world’s most comprehensive guide to the extinction risk of animals.

Vincent also partnered with local communities and biologists, industry groups, aquariums and governments around the world to develop sustainable approaches to seahorse trade, rather than work to ban all trade outright.

The approach allowed her to motivate Australia to regulate the extraction of seahorses and similar fishes, and prompted the Hong Kong Chinese Medicine Merchants Association to implement a voluntary code of conduct for seahorse imports.

In the Philippines, she initiated an alliance of 1000 small-scale fishing families to co-manage seahorses and helped create 35 marine protected areas – dedicated areas of the ocean where no fishing is allowed and the populations of seahorses and other marine fishes thrive.

“It turned out that we wanted the same thing as the local fishers – for there to be enough seahorses that you can fish off a few without losing entire populations,” said Vincent.

Then, in 2002, she played an instrumental role in persuading the United Nations Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) to adopt milestone legislation to limit global seahorse trade to sustainable and legal exports, with seahorses becoming the first marine fishes to be included since the inception of the Convention in 1976.

Together, these efforts furthered the legitimacy of marine conservation and created policies to effectively and sustainably manage fisheries all over the world. As of 2018, countries that previously exported 96 per cent of dried seahorses had suspended trade.

“People didn’t see fish as wildlife, but Amanda changed that,” said Sarah Foster, a long-time collaborator and project manager at Project Seahorse.

Vincent’s greatest contribution to marine conservation may be the people she has inspired along the way, from school children to businesses like Guylian Chocolates Belgium, which has funded Vincent’s research and conservation activities for more than 20 years.

Since 1996, Vincent and Project Seahorse – which was established in partnership with the London Zoological Society, have trained more than 175 professional conservationists and inspired countless amateur conservation advocates to contribute through a citizen science program call iSeahorse.

Today, there are active seahorse conservation projects across six continents – most of them inspired by Vincent’s work – and draw on her advice as chair of the IUCN global expert group on seahorses, pipefishes and seadragons.

She and her Project Seahorse team are now focused on bringing an end to the harmful fishing practice that is the single biggest threat to seahorses – bottom trawling – where industrial nets are dragged across the ocean floor, catching all life in their path and destroying vital habitats such as coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds. Project Seahorse estimates that more than 70 million seahorses are ripped from the ocean by trawls and other nonselective fishing gear every year.

“This waste of life has to stop – we’re allowing devastation of our oceans in a way that we would never permit on land,” said Vincent. “Through the perspective of seahorses, we have inspired many, many people globally to safeguard ocean life. The Indianapolis Prize now gives us an even bigger platform to invite and empower people to take meaningful conservation action.”

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation