Single-celled predator evolves tiny, human-like 'eye'

July 1, 2015

July 1, 2015

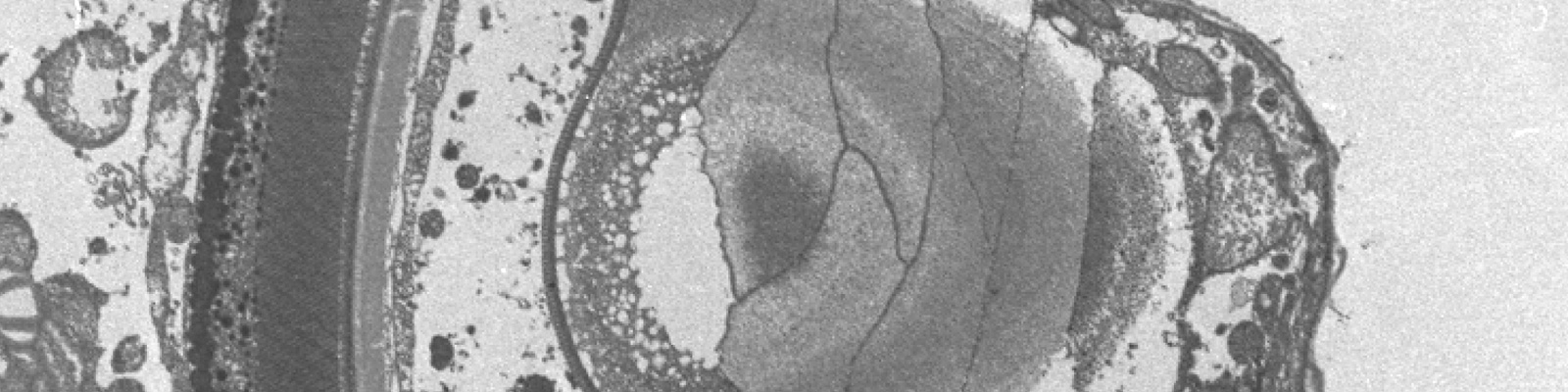

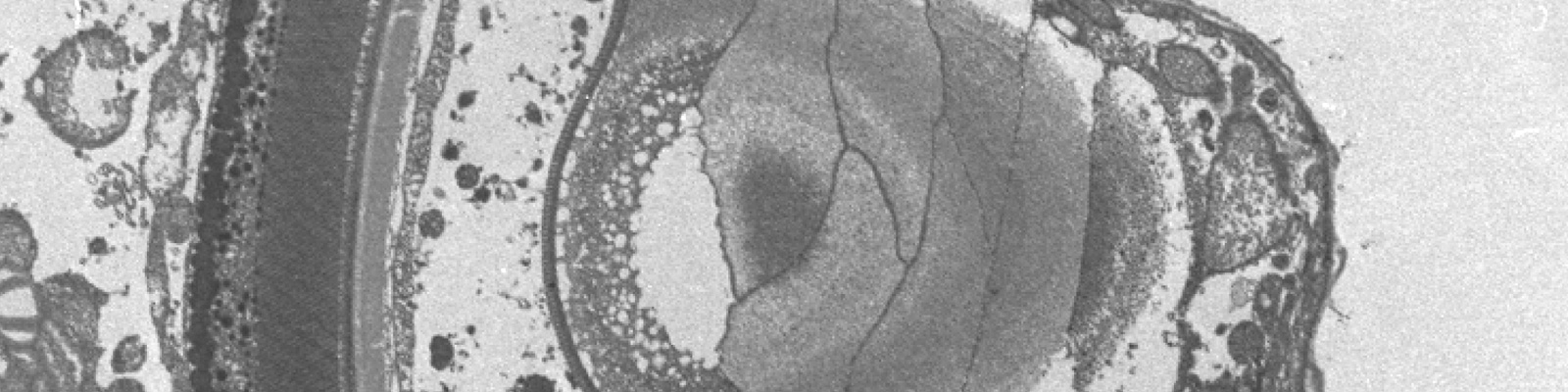

A single-celled marine plankton evolved a miniature version of a multi-cellular eye, possibly to help see its prey better, according to University of British Columbia (UBC) research published today in Nature. In fact, the 'ocelloid' within the planktonic predator looks so much like a complex eye that it was originally mistaken for the eye of an animal that the plankton had eaten.

“It’s an amazingly complex structure for a single-celled organism to have evolved,” said lead author Greg Gavelis, a zoology PhD student at UBC. “It contains a collection of sub-cellular organelles that look very much like the lens, cornea, iris and retina of multicellular eyes found in humans and other larger animals.”

Scientists still don’t know exactly how the marine plankton, called warnowiids, use the eye. Warnowiids use small harpoon-like structures to hunt prey cells in the plankton, many of which are transparent.

The researchers speculate that the eye helps warnowiids detect shifts in light as it passes through their transparent prey. The structure could then send chemical messages to other parts of the cell, showing them in which direction to hunt.

“The internal organization of the retinal component of the ocelloid is reminiscent of the polarizing filters on the lenses of cameras and sunglasses,” said UBC zoologist Brian Leander, senior author on the paper. “It has hundreds of closely packed membranes lined up in parallel.”

The researchers—including the labs of UBC microbiologist Patrick Keeling and virologist Curtis Suttle—gathered samples of warnowiids off the coasts of B.C. and Japan.

The team analyzed the eye-like structure using state of the art microscopy at the Centre for High-Throughput Phenogenomics at UBC. The microscopes enable the reconstruction of three dimensional structures at the subcellular level.

The work sheds new light on how very different organisms—in this case warnowiids and animals—can evolve similar traits in response to their environments, a process known as convergent evolution.

“When we see such similar structural complexity at fundamentally different levels of organization in lineages that are very distantly related, then you get a much deeper understanding of convergence,” says Leander.

The research was supported by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the Tula Foundation, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation