Need for speed: How hummingbirds switch mental gears in flight

January 10, 2024

January 10, 2024

Hummingbirds use two distinct sensory strategies to control their flight, depending on whether they’re hovering or in forward motion, according to new research by University of British Columbia (UBC) zoologists.

“When in forward fight, hummingbirds rely on what we call an ‘internal forward model’—almost an ingrained, intuitive autopilot—to gauge speed,” says Dr. Vikram B. Baliga, lead author of a new study on hummingbird locomotion published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. “There’s just too much information coming in to rely directly on every visual cue from your surroundings.”

“But when hovering or dealing with cues that might require a change in altitude, we found they rely much more on real-time, direct visual feedback from their environment.”

The findings not only provide insights on how the tiny, agile birds perceive the world during transitions in flight, but could inform the programming of onboard navigation for next generation autonomous flying and hovering vehicles.

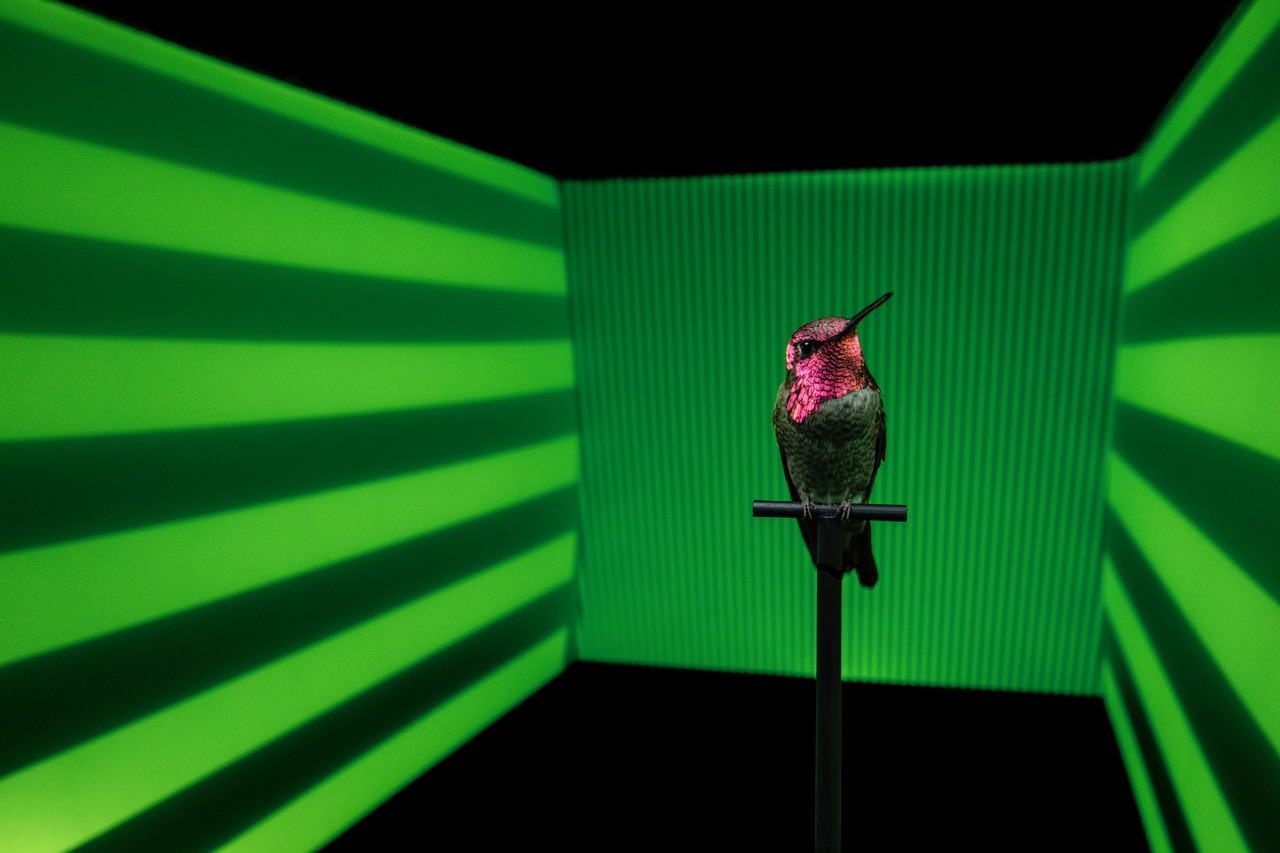

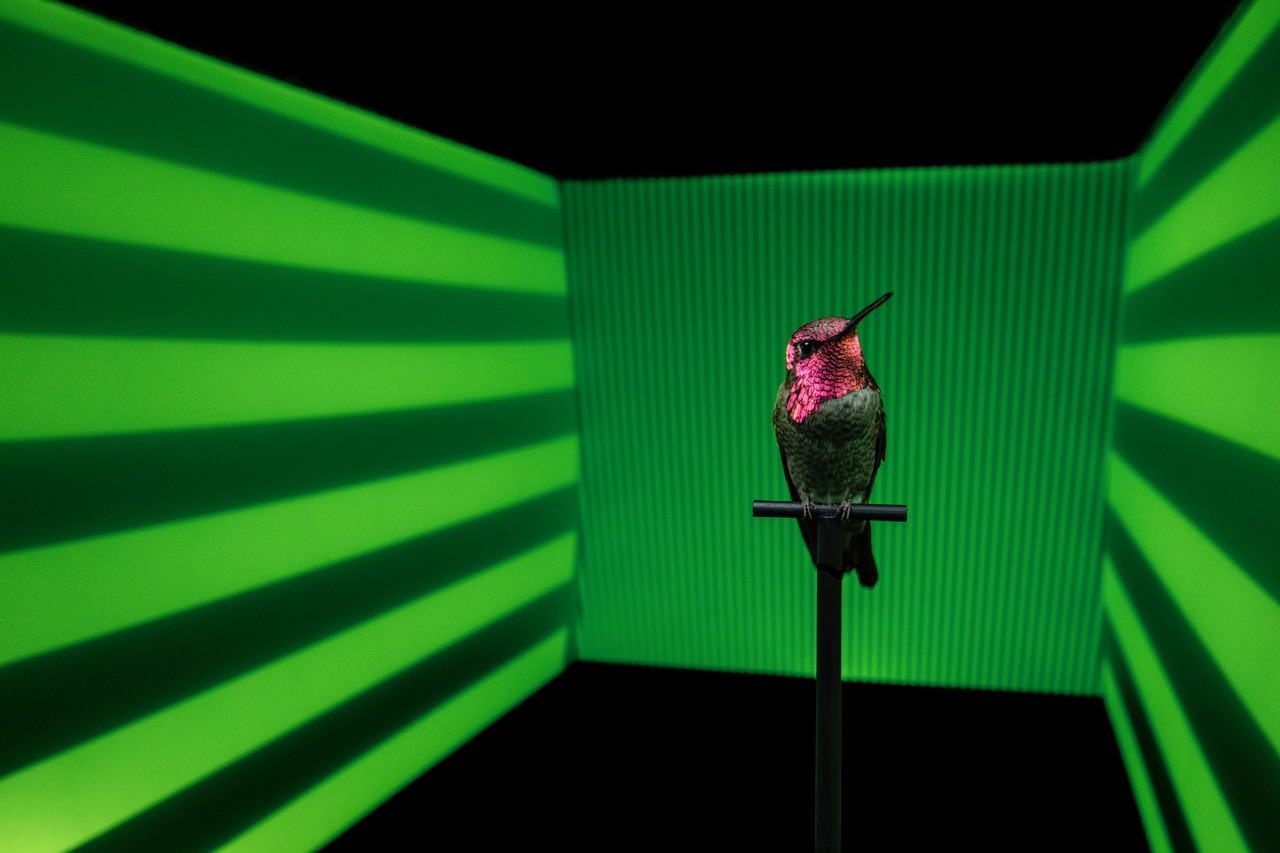

The researchers had hummingbirds perform repeated flights from a perch to a feeder in a four-metre tunnel. To test how the birds reacted to a variety of visual stimuli, the team projected patterns on the chamber’s front and side walls. Each flight was videoed.

In some scenarios, the researchers projected vertical stripes moving at various speeds on the side walls to mimic degrees of forward motion. Sometimes, horizontal stripes on the side mimicked changes in altitude. On the front wall, the researchers projected rotating swirls, designed to create the illusion of a change in position.

“If the birds were taking their cues directly from visual stimuli, we’d expect them to adjust their forward velocity to the speed of vertical stripes on the side walls,” says Dr. Baliga. “But while the birds did change velocity or stop altogether depending on the patterns, there wasn’t a neat correlation.”

However, during flight, the hummingbirds did adjust more directly to stimuli indicating a change in altitude. And during hovering, the birds also worked to adjust their position much more closely to shifting spirals the research team projected on the front wall.

“Our experiments were designed to investigate how hummingbirds control flight speed,” says Dr. Doug Altshuler, senior author on the paper. “But because the hummingbirds took spontaneous breaks to hover during their flights, we uncovered these two distinct strategies to control different aspects of their trajectories.”

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation