Rising world temperatures will cause most populations of herbivores – including plant-eating fish – to decline, according to a University of British Columbia biologist.

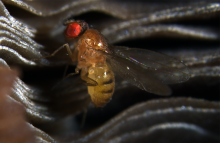

That prediction resulted from updated mathematical models that integrate fundamental biological effects of temperature with the way herbivores and plants interact. These models were combined with data from experiments using “mini-ecosystems” of phytoplankton (aquatic microscopic plants) and zooplankton (aquatic microscopic animals) co-existing in four-litre tanks set to different temperatures over eight days.

As expected, higher temperatures increased the metabolisms – the conversion of resources to energy – of both plants and animals, but the effect on animal metabolisms was more intense. The zooplankton consumed more phytoplankton as a result.

But the plants could not keep pace with the animals’ increased appetites, and the lack of food ultimately led to a decline in the animals’ numbers.

“Herbivores are going to need more food than the plants are making just because of the higher temperatures,” says Mary O’Connor, an assistant professor of zoology who co-authored the article, published online today by The American Naturalist. “Eventually, the system is limited by how fast the plants can grow.”

O’Connor, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral associate at the National Center for Ecological Analysis & Synthesis in Santa Barbara, California, predicts that a rise of 3 degrees Celsius, which is forecast for many regions over the next century, could cause a 10-per-cent decline in herbivores.

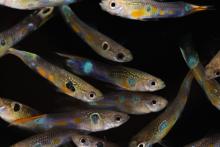

In tropical oceans, this would likely mean a decline of plant-eating fish and crustaceans, with the possibility of corresponding declines of fish higher in the food chain – and an eventual decrease in seafood supplies in some parts of the world’s warmer oceans.

The effect in colder areas, like the northern Pacific, would be less severe because warming is expected to increase the supply of nutrients in those waters. The abundance of nutrients would enhance the growth of plants, allowing them to keep pace with animals’ increased appetites.

O’Connor, a member of the UBC Biodiversity Research Centre, says the findings could apply to land-based ecosystems as well but the implications are more difficult to predict because the thermal environment is more complex.

These findings are much more “big picture” than many previous experiments or models of global warming’s effects on plants and animals, which have focused on particular species – with widely varying results, O’Connor says.

“I’m backing way out, looking for something in common among all of species,” she says. “And what we’re suggesting is that we can expect herbivores, en masse, to decline, even though some species of herbivores might increase and others might decrease. By looking at it from this perspective, we will get a clearer picture of what is likely to happen.”

Musqueam First Nation land acknowledegement

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation

Faculty of Science

Office of the Dean, Earth Sciences Building2178–2207 Main Mall

Vancouver, BC Canada

V6T 1Z4