Mathematicians model a puzzling breakdown in cooperative behaviour

September 3, 2024

September 3, 2024

Darwin was puzzled by cooperation in nature—it ran directly against natural selection and the notion of survival of the fittest. But over the past decades, evolutionary mathematicians have used game theory to better understand why mutual cooperation persists when evolution should favour self-serving cheaters.

At a basic level, cooperation flourishes when the costs to cooperation are low or the benefits large. When cooperation becomes too costly, it disappears—at least in the realm of pure mathematics. Symbiotic relationships between species—like those between pollinators and plants–are more complex, but follow similar patterns.

But new modelling published today in PNAS Nexus adds a wrinkle to that theory, indicating that cooperative behaviour between species may break down in situations where, theoretically at least, it should flourish.

“As we began to improve the conditions for cooperation in our model, the frequency of mutually beneficial behaviour in both species increases, as expected,” says Dr. Christoph Hauert, a mathematician at the University of British Columbia who studies evolutionary dynamics.

“But as the frequency of cooperation in our simulation gets higher—closer to 50 per cent—suddenly there's a split. More cooperators pool in one species and fewer in the other—and this asymmetry continues to get stronger as the conditions for cooperation get more benign.”

While this ‘symmetry breaking of cooperation’ between two populations has been modelled by mathematicians before, this is the first model that enables individuals in each group to interact and join forces in a more natural way.

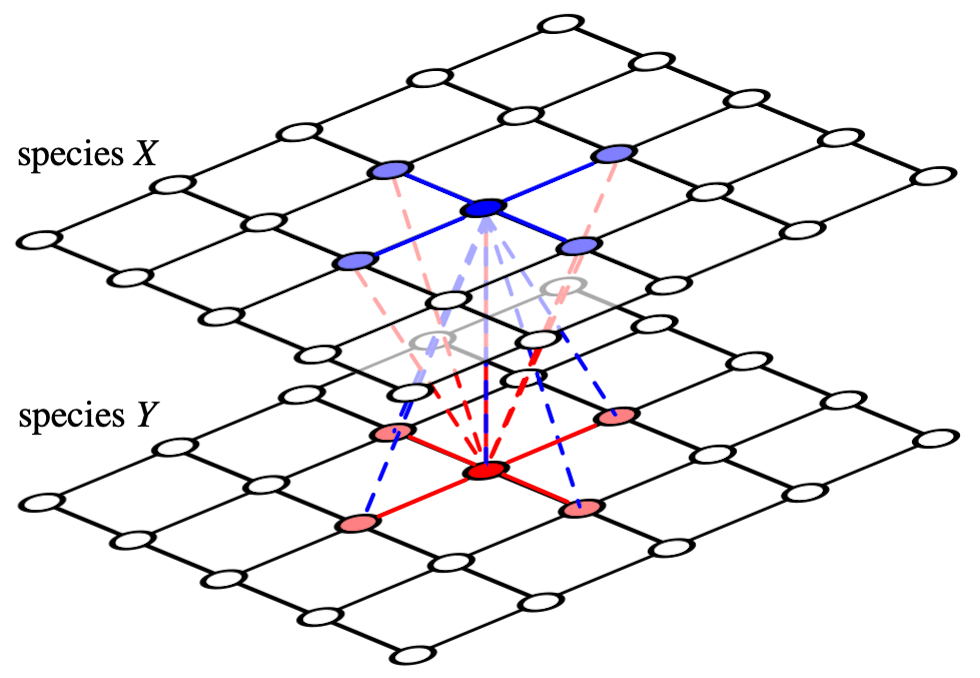

Dr. Hauert and colleague Dr. György Szabó from the Hungarian Research Network used computational spatial models to arrange individuals from the two species on separate lattices facing one another. This enables cooperators to form clusters and reduce their exposure to (and exploitation by) cheaters by more frequently interacting with other cooperators.

“Because we chose symmetric interactions, the level of cooperation is the same in both populations,” says Dr. Hauert. “Clusters can still form and protect cooperators but now they need to be synchronized across lattices because that’s where the interactions occur.”

"The odd symmetry breaking in cooperation shows parallels to phase transitions in magnetic materials and highlights the success of approaches developed in statistical and solid state physics,” says Dr. Szabó.

"At the same time the model sheds light on spikes in dramatic changes in behaviour that can significantly affect the interactions in complex living systems."

The research was supported by the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

A model developed by evolutionary mathematicians in Canada and Europe shows that as cooperation becomes easier, it can unexpectedly break down. Watch a simulation of spatial interactions of cooperators and defectors for each species under different scenarios.

We honour xwməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam) on whose ancestral, unceded territory UBC Vancouver is situated. UBC Science is committed to building meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples so we can advance Reconciliation and ensure traditional ways of knowing enrich our teaching and research.

Learn more: Musqueam First Nation